If you had to pick just one icon of American sports car performance, it’s a safe bet that the Corvette would be on everyone’s list. And while there are many examples from nearly 70 years of history, perhaps the most exciting Corvette to ever come to market was the 1963 Split window Sting Ray.

It’s certainly easy to view the Corvette as one of many advanced sports car designs that emerged in the 1950s, but the Spilt Window Coupe prevails as a dramatic shift from everything that was happening in car design at that time, ushering in a wide range of fresh, chiseled body designs that continue to impress more than half a century later. In addition to the radical design, the all-new 1963 Corvette set a high standard for performance excellence at a reasonable price. Distinguishing itself in both competition and on the street, uniquely aligned with the racing energy from those who created it.

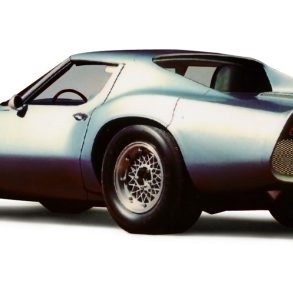

The story of the Split Window Corvette has been told many times but it’s important to note that the design was both revolutionary and evolutionary in a number of ways. In 1957, the impossibly young Peter Brock, then just 19-years old, became the youngest designer hired at GM’s Styling Department. There, under the tutelage of Bill Mitchell, Brock sketched the initial concept which would later become the Stingray Racer.

Even though this early iteration was very different from what would eventually become the Split Window Coupe, key design elements were already featured in this unique and innovative design. Capturing themes seen in European designs including the Alfa Romeo Disco Volante, the distinctive flat hood, central hood bulge, perimeter body crease, and clean lines were an instant departure from the formerly rotund and curvaceous designs seen in cars of the 1950s. Brock’s concept not only signaled to the public that sports car design was about to change, the most impressive follow through came when Mitchell declared that this was going to be the future design theme for the Corvette.

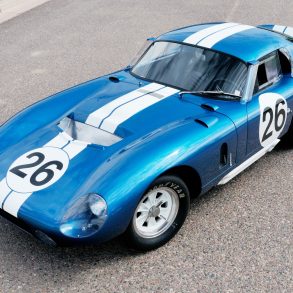

Brock, perhaps eager to work outside of the restrictive confines of the corporate environment, departed from GM and headed west where he would become the first Shelby American employee and a seminal figure in the development of the Shelby Daytona Coupe. An entire article could be crafted solely on the impact of these two cars, both of which changed sports car history in many ways, all before Brock was 30-years old.

With deadlines approaching and much to do back at GM, Mitchell selected his next designer as the key man to refine the Sting Ray Racer into a viable production car. Larry Shinoda had just the right level of enthusiasm and grit to bring the car to life. Shinoda, of Japanese descent, struggled as a child, confined for years to the War Relocation Camp at Manzanar, California. Full of curiosity and compelled to draw performance cars, Shinoda became involved in drag racing, hot rods, and custom cars. His pent-up anger and competitive ferocity became legendary. And his pulse on the So Cal car scene was ideal for GM, despite his often-hot temper. Fueled by Mitchell’s appreciation for speed and performance, Shinoda was tasked with transforming the Sting Ray Racer into a viable production car. After penning the Mako Shark Show Car, Shinoda focused on subtle changes to the body design, the biggest and most iconic being the addition of the Split Window feature.

Inspired by Mitchell and rumored for years to have been referenced in the split rear glass of the 1938 Adler Trumpf Rennlimousine, this rare car reportedly spent time at the GM Styling center while Shinoda worked on the final design. And while it is certainly thematically evident, this was not the only split window design known at the time. In any case, while it’s clear that Shinoda was aware of the idea, he incorporated very different ideas articulating the rear glass, the central spine, and the unique race-inspired features that would complete the car.

Though Brock had delivered a key part of the design in the Sting Ray Racer, Shinoda applied refinement and care to every surface of the final design. Shinoda not only created a stunning coupe, he solved the design problem of designing a harmonious roadster that retained the character of the original Sting Ray Racer and Mako Shark. The final design was so compelling and, with new technical features, performance improvements, and desirable suspension and brake enhancements, the Sting Ray would go on to dominate with sales nearly doubling in 1963 from the previous year, and continuing for five more years until the Mako Shark II influence would usher in the new C3 body design.

Looking at the 1963 Corvette today there are three major design themes that deliver the power and presence of this car. Perhaps the least appreciated is the scale of the wheels and tires tucked under the wheel openings, separated by a mere 98” wheelbase the car has a powerful presence. Both Shinoda and Brock used the wheel and tire combination as a muscular visual signatures to enhance the performance of the car. Shinoda worked with a more modest wheelbase and engine package/placement while the racecar had a far more elongated presence. Shinoda crafted a near bulldog stance with the ’63 Corvette, upright and muscular, able to take on all contenders. The profile’s spunkiness is further supported with the boattail arrowhead tip at the rear of the car.

Here, Shinoda echoes the central hood spear, uniting the themes with a delicately raised central spine, while delineating the upper side panel vents and roof vents as unified racing themes. Lastly, the chiseled perimeter belt line divides the top and bottom surfaces with a pinched swelling that adds significant width to the rather small car, enhancing the stance, width, and musculature in the fender bulges. Of course, these themes were critical to the success of the design, but so many other features further cemented the ’63 Corvette as an icon of performance, including pop-up headlights, a range of performance engines, race-inspired instrumentation, and independent rear suspension. The 1963 Corvette was not only innovative as a design, it set the standard for all Corvettes for decades to come.

The Split Window design would sadly remain in production for just one-year, eventually succumbing to complaining buyers and GM legal advisors worried about partially obscured rear vision. Many owners, upon seeing the 1964 version without the split, removed the rear glass, cut the central spine, and installed 1964 single-piece rear glass. Thankfully, most if not all of those cars have been mercifully restored to correct Split Window status.

Visually stunning and innovative in every respect, the youthful design vision from Brock, Shinoda intensity, their mutual love of performance, and Bill Mitchell’s willingness to take a risk on something truly dramatic, makes the 1963 Split Window Corvette one of the most important and successful sports car designs of the 20th century.