In early 1900, a Mr. Kenneth Skinner, from Boston was granted an exclusive license by the De Dion Company to sell and manufacture its automobiles in America. He was already importing their stationary engines and selling De Dion tricycles. He licensed a new American company The De Dion Motorette Company of New York to make the cars, a company with a stock capital of $750,000 of which $150,000 was cash. And so the designate General Manager of the Motorette Company, Cornelius Field, traveled to Paris in June 1900. Production of De Dion cars in France was now well under way. Mr. Field returned to New York a month later accompanied by drawings, parts and 3 cars. In that year only 25 cars were imported into the U.S. There was a crippling 45% import duty on self-propelled vehicles.

Field had an impeccable engineering background, he had supervised the introduction of electric lighting (using the new “electric fluid”) at the White House and had helped develop, with financier Patrick H Flynn, the successful Nassau Electric Railway Company – a railway connecting Brooklyn to central New York. In 1899, the Nassau Railway and the New York Transit Company merged, and as a result Nassau’s railway sheds in Brooklyn were vacated. It was here that Cornelius Field with father-in-law William Craven and business partners Flynn and Fred Cochew, setup the Motorette Company’s offices and workshops. There were only 8000 automobiles registered in the United States at the time.

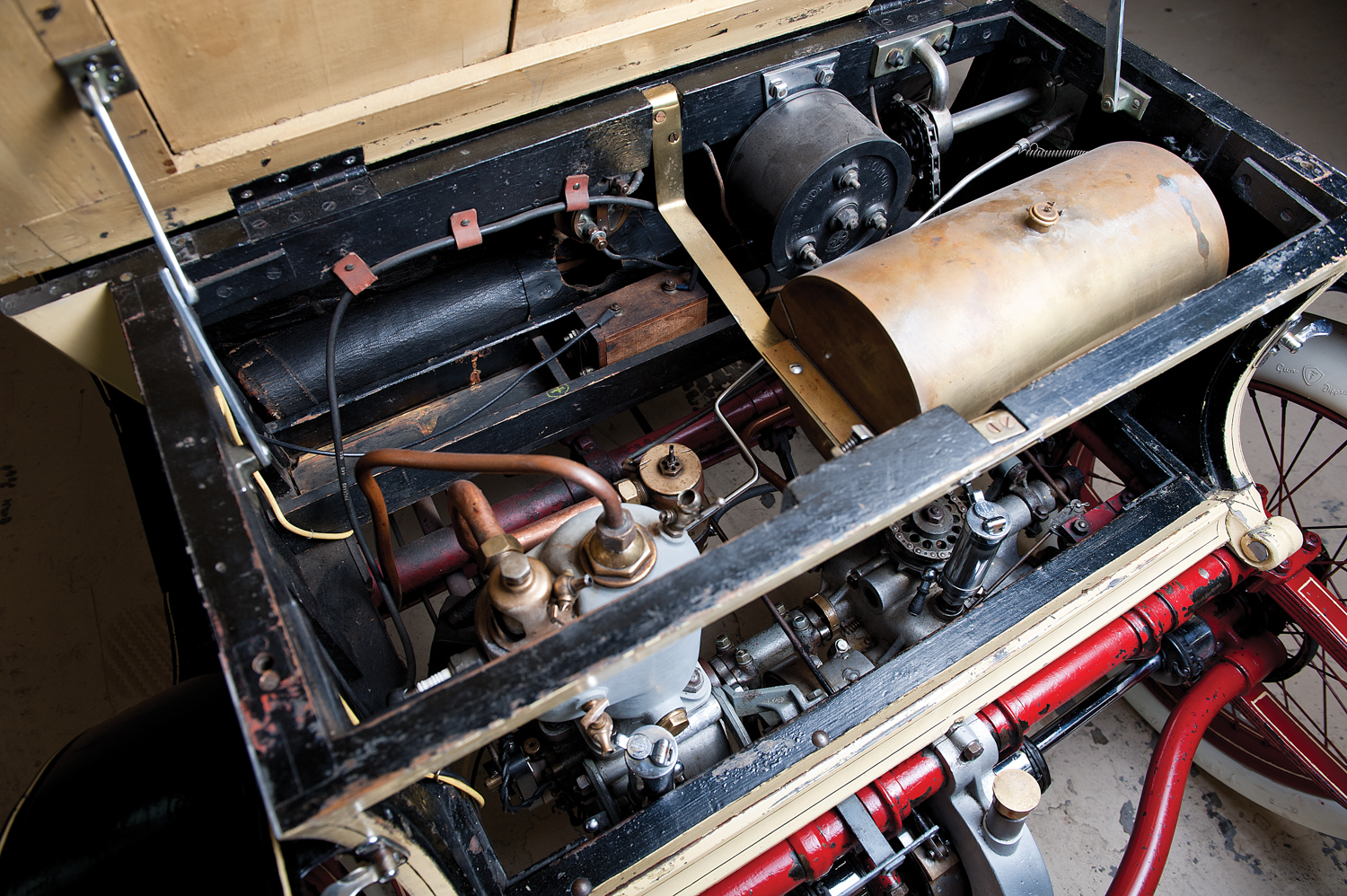

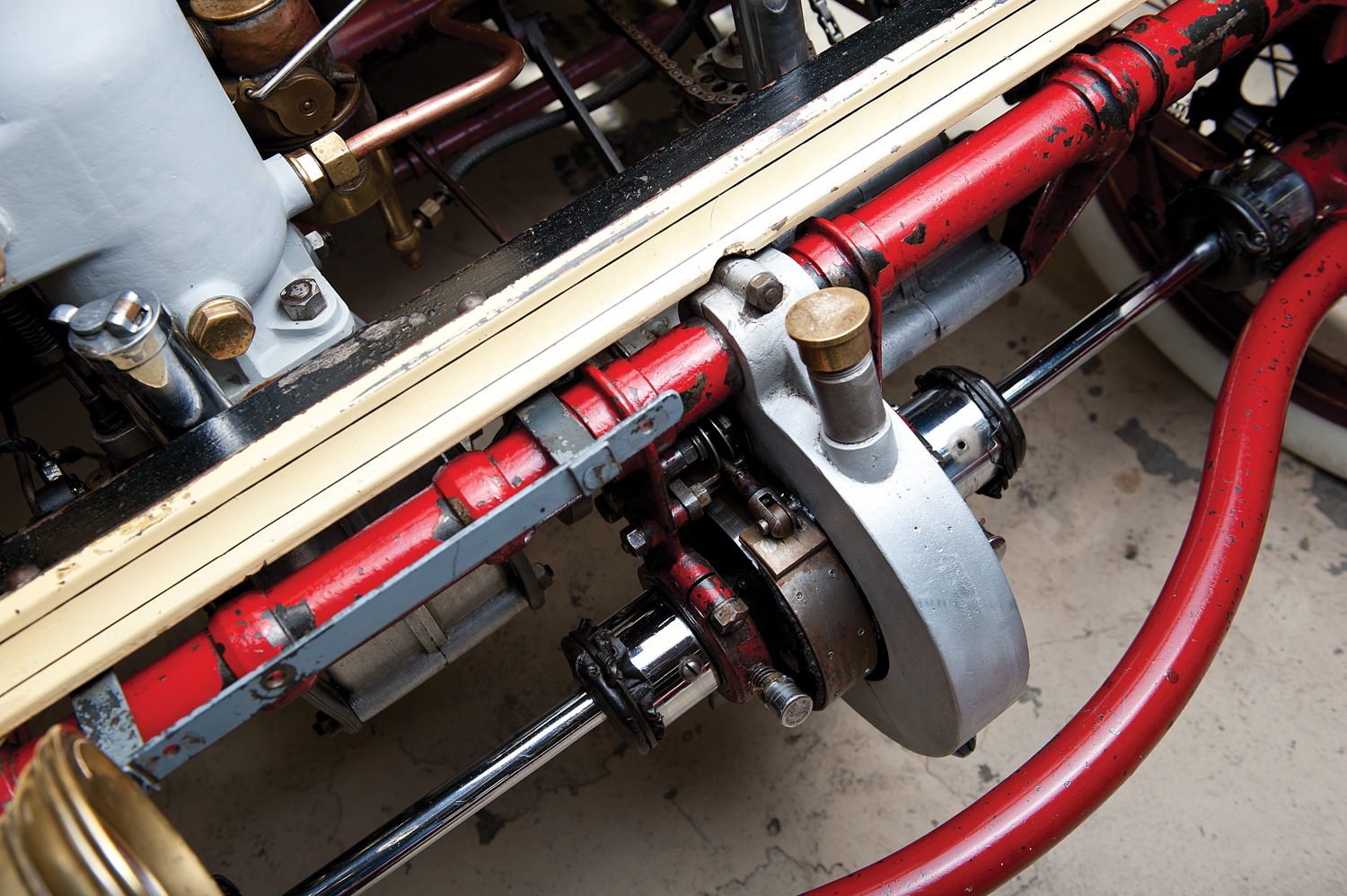

It is perhaps surprising that electrical engineer Field had decided to favor the internal combustion engine rather than electrical or even steam power. In fact, half of the automobiles in the U.S. at that time were steamers, the American Locomobile was the most popular – despite its limited range of 20 miles on one tank of water, and its propensity to self ignite! However, at $750 it was comparatively cheap, and popular and cheerful, Rudyard Kipling publicly described his machine as a “nickel plated fraud”. Simplicity was the hallmark of the steamer (and, indeed the electrical automobile); gear changes were unnecessary and the high torque at slow speed made them well suited to America’s poor roads. A car powered by an internal combustion was a novelty, a far more sophisticated vehicle than an electric or steam car. It was an engineer’s motor car, no doubt Motorette engineer Cornelius Field was excited by its sophistication – with the advanced high revving engine, unique De Dion back axle and the high tension electrical ignition. But was it too revolutionary and sophisticated for the times?

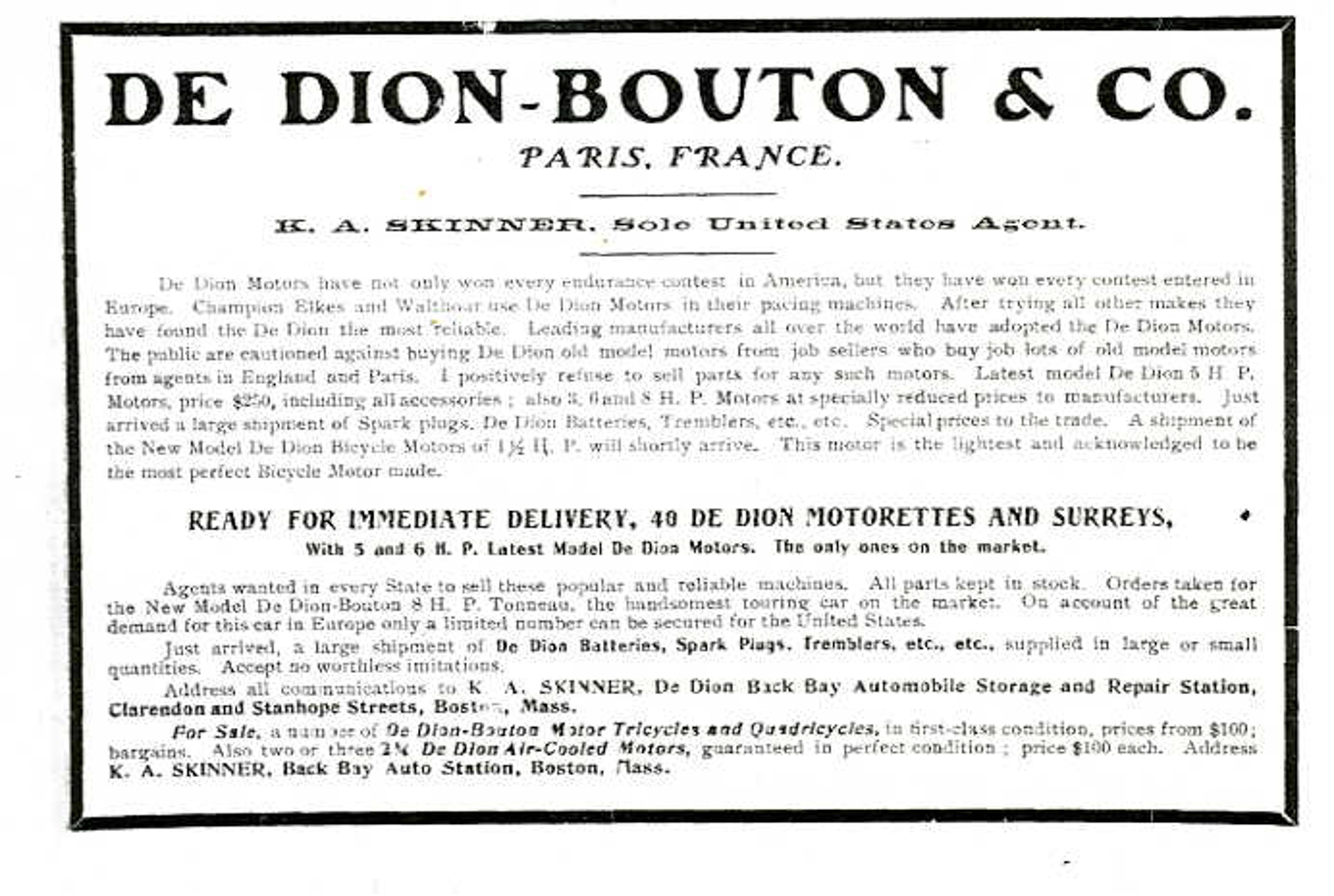

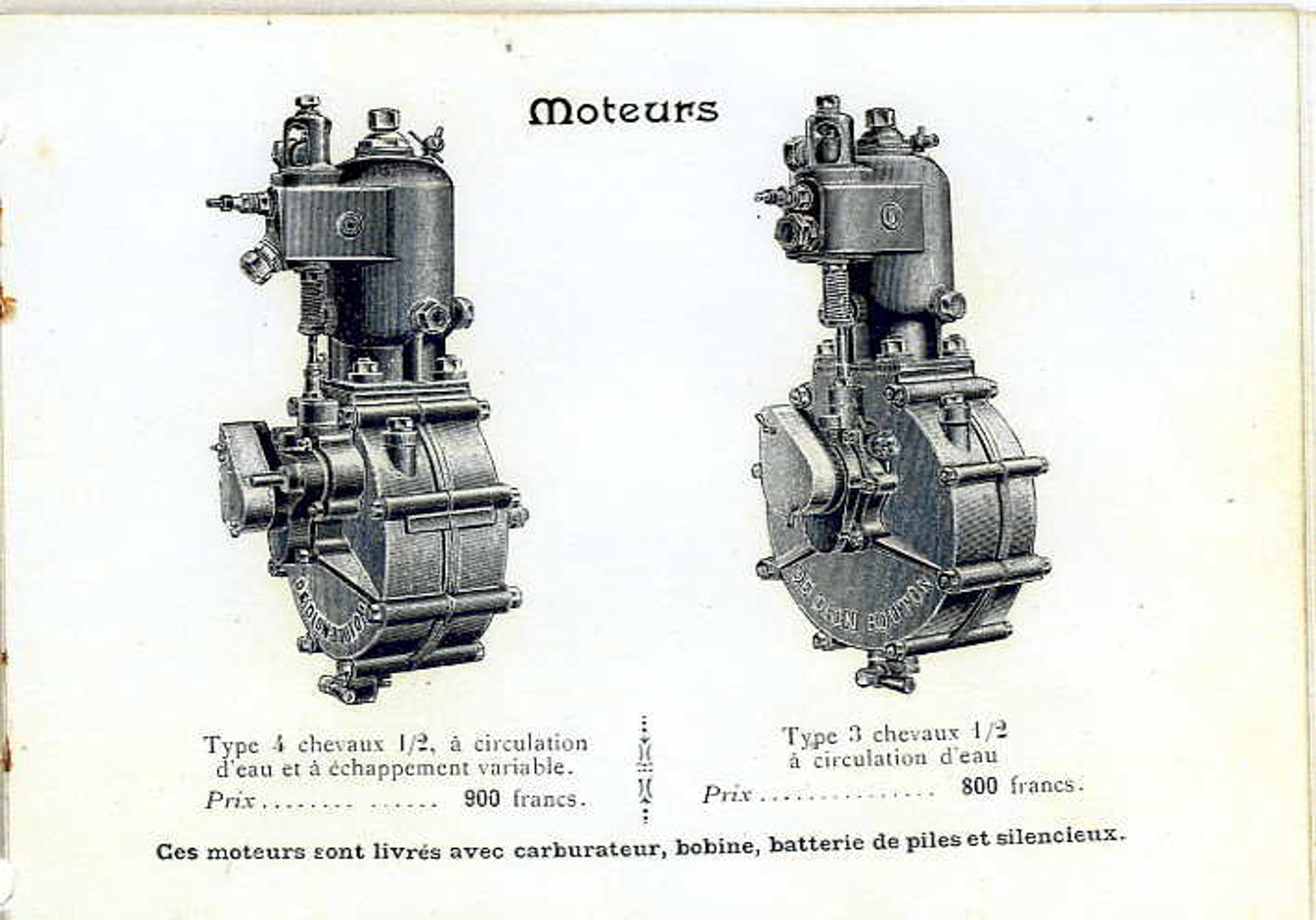

There were only 500 cars registered (voluntarily) in New York and Brooklyn when the Motorette Company started business. The market was ready to be exploited with a quality automobile for the discerning customer – the future looked rosy for the American Motorette Company. A major publicity campaign began with full-page adverts in the three U.S. motoring magazines. The Motor Car Journal referred to the De Dion engine as the best in the world. It was well respected, in the States as a stationary engine powering generators and small items of machinery. The respected Peerless Automobile Company had adopted De Dion engines and with much advertising an imported French Panhard was modified to take a De Dion engine. In September 1900, just before production began, De Dion Motorettes and Quadracycles won all their competitive events at the Guttenburg Fair in New York.

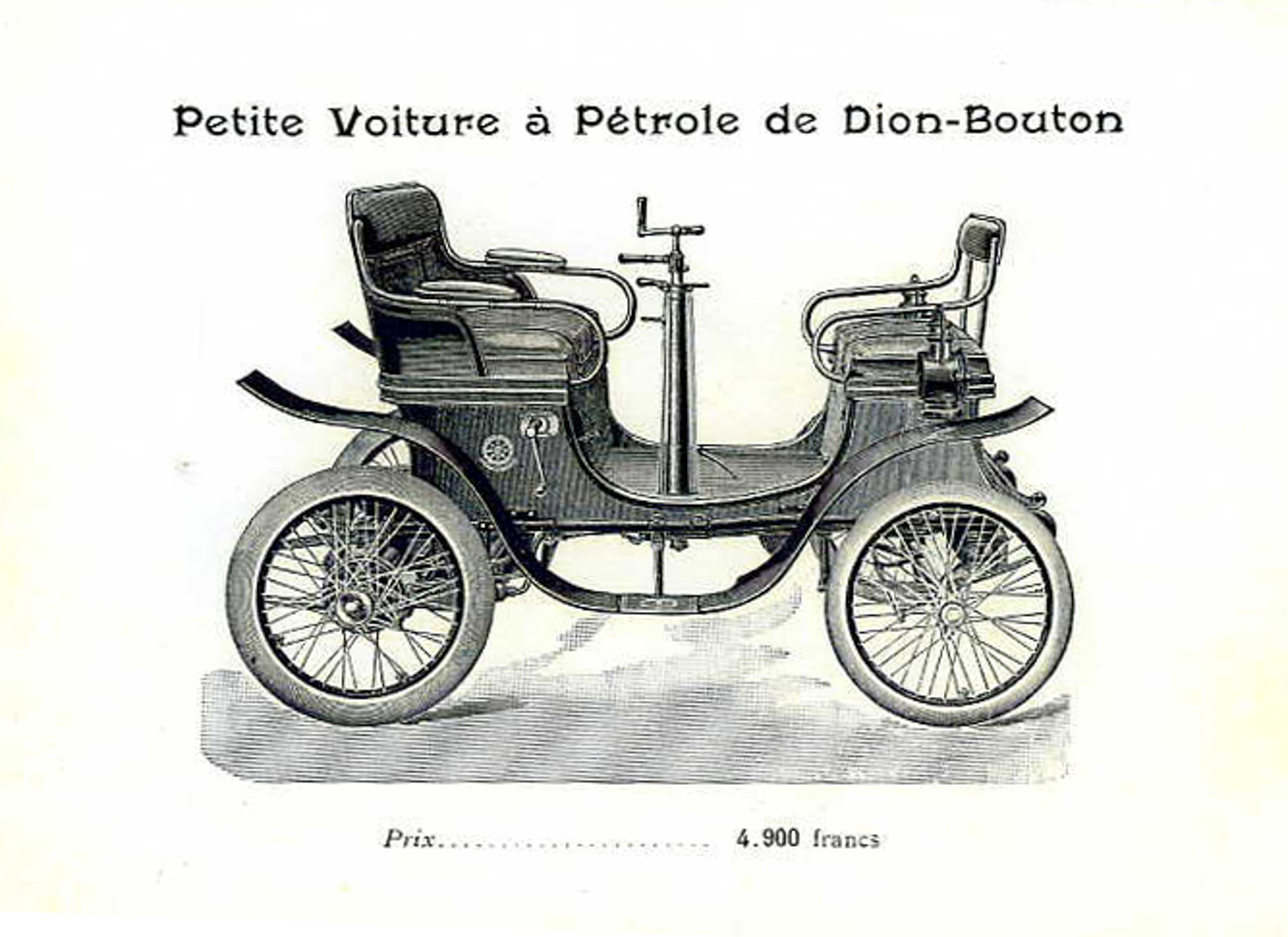

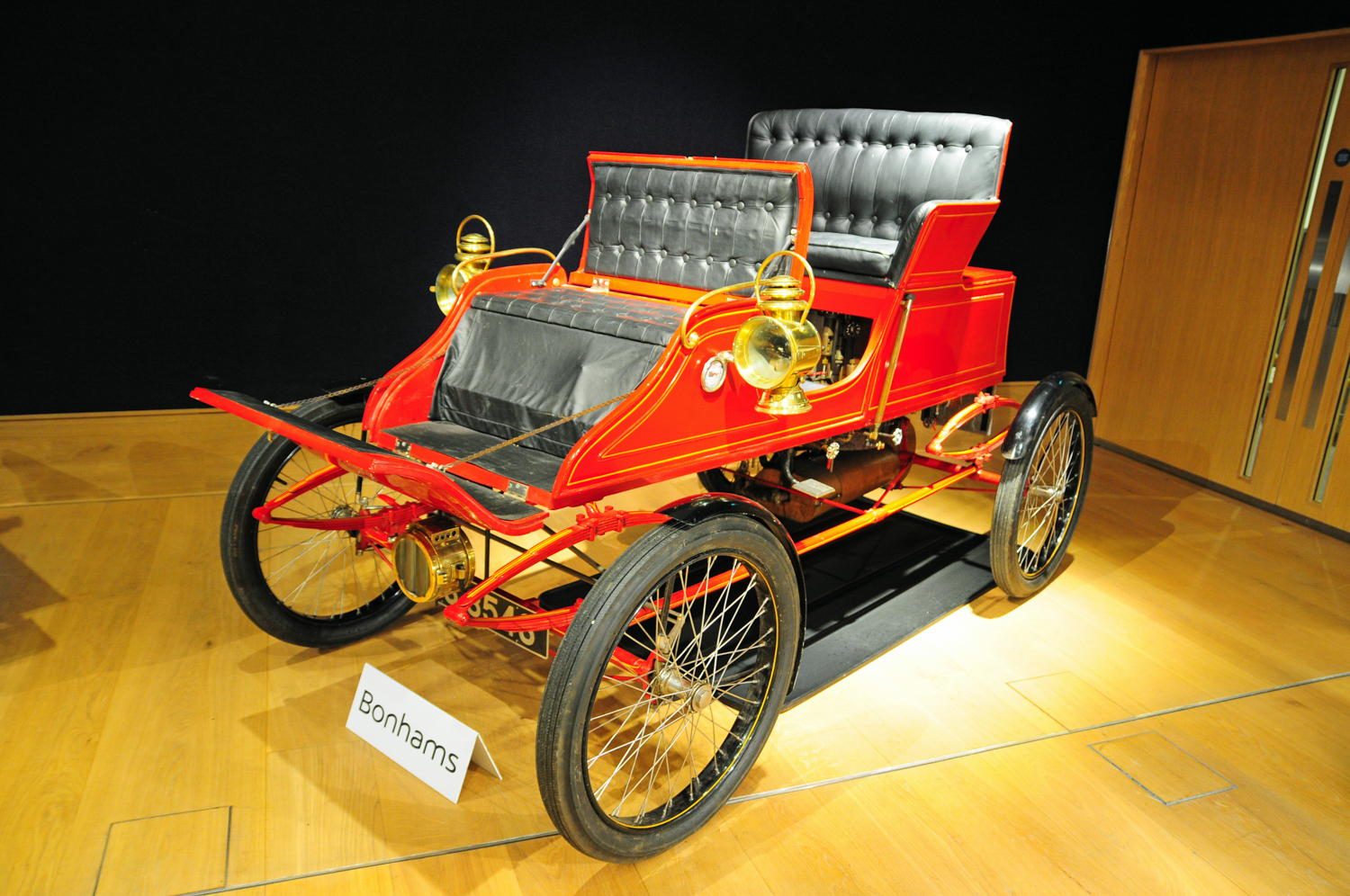

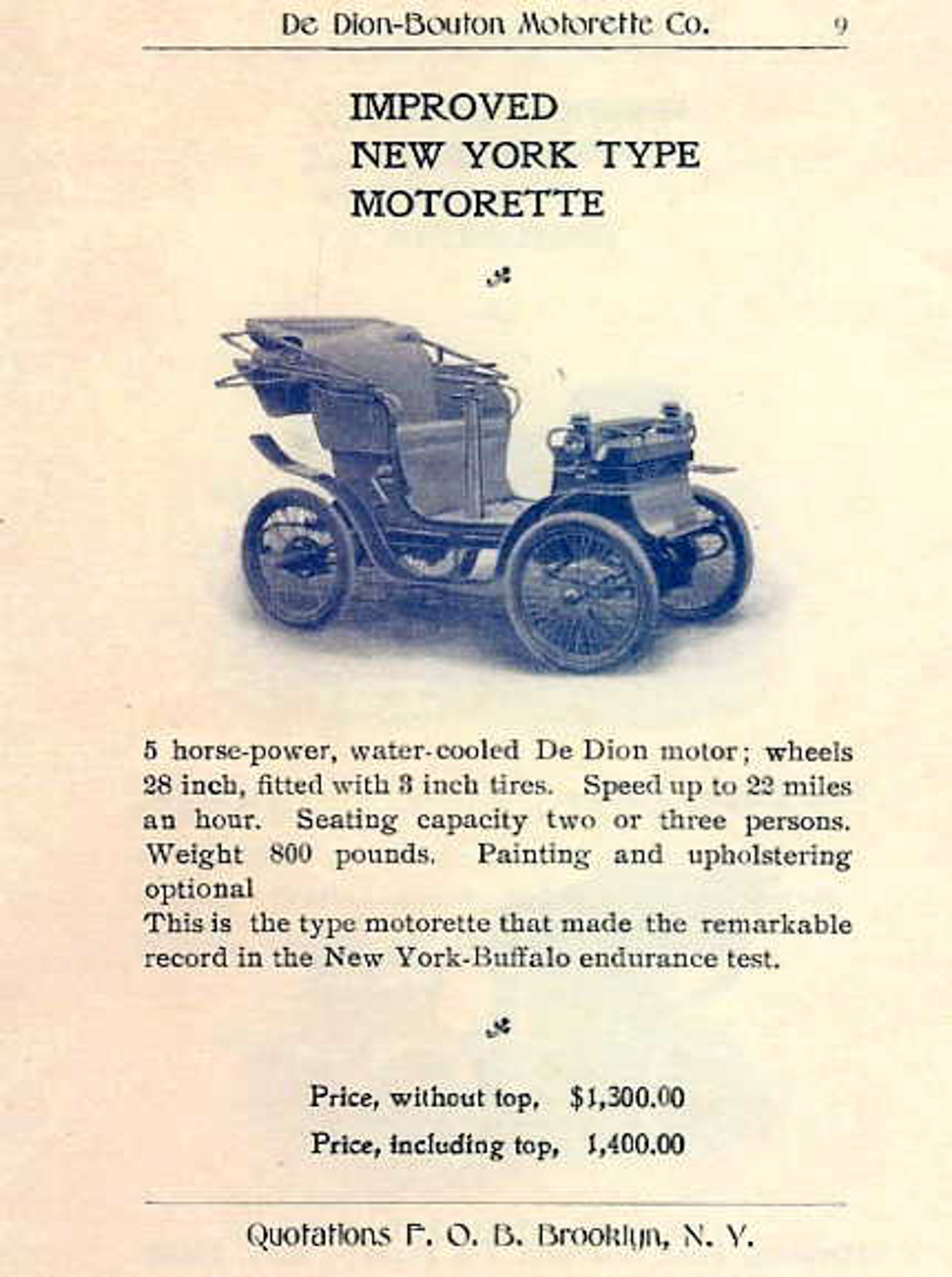

The New Year of 1901 saw the Company announce, two months late, “that owing to the completion of our manufacturing plant…we are in a position to assure customers of our unequalled facilities for the prompt execution of orders.” The automobile on offer was a copy of the French Vis-à-Vis called the New York Motorette, type No 1 had a 3 1/2 hp engine and type No 2 a 5hp engine. These models had a rear luggage rack with fold down front seats; features which exist in all the surviving Motorettes. These cars could be ordered in any color with any modification requested by the purchaser. One we know had wooden wheels instead of wire and one a steering wheel.

“The vehicles have been met with a gratifying reception and we have already had the pleasure of supplying Motorettes to many commercial leaders of New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia and elsewhere, there is hardly a large city in which a Motorette will not be seen.” This was an influential clientele who would not be pleased if their internal combustion engined automobile did not match up to expectations. Certainly the simple gearbox, immediate starting (which a steamer had not) and the reliable advanced ignition system made it good value even at the increased price now of $1300-1400. But all was not well…

In Feb 1901, William Morgan, who owned the Autocar Company of Pennsylvania, took The Motorette Company to task in the press for claiming that their machine could match any vehicle weighing twice as much. “The American public must not accept too blindly the theories and practices which dominate in France. The finest roads in France are equal to the finest Macadam boulevards in America and within a 50 mile radius of Paris a grade exceeding 20% cannot be found…it is almost impossible to start them from a standing start without using what is known as the hill climbing gear,” this in a two speed machine was, of course, not a “fault”.

Prejudice was beginning too grow and later in that year real competition appeared in the crude but very practical internal combustion engined Curved Dash Oldsmobile; with large wheels, high ground clearance, wide track and a high torque low speed engine. It was half the price of the much more sophisticated but somewhat “mysterious” De Dion Motorette – a car which featured entirely enclosed mechanics and the even more mysterious high tension coil ignition system. The De Dion was a machine, perhaps, too sophisticated for the general artisan mechanic. The company may well have been aware of this, for the June 1901 sales catalogue pointed out “we have tried to anticipate the little troubles that are likely to be met with until the operator has learned by experience the knack of driving the Motorette.” At the same time changes were made to the car, with heavier springs and larger bearings all no doubt necessary after the pounding the cars received on American roads.

In the same month of June The Brooklyn Eagle reported that 10 members of the Long Island Automobile Club had organized a two-hour run to the Garden City Hotel in New York. (Long Island had some of the best roads in the country and well suited to light voiturettes) “However, man proposes only, and but two of those that left Brooklyn reached their destination” a De Dion and a steam Locomobile. Unfortunately, three De Dion Motorettes, three Locomobiles and two electric cars failed to complete the two hour journey. One De Dion was driven by Cornelius Field from the Motorette Company and a committee member of the organizing Club. In September, four De Dions were entered into the New York to Buffalo Endurance Run a distance of about 300 miles. Two De Dions gained first and second class awards, but it appeared that four cars were advertised as entered but only two finished. The company claimed that two cars had not appeared at the start line. Curiously, one of the Motorettes was driven by a Mr. J Lauegez and a Mr. C Lanngumen ex Panhard agents. Laungamen had tried to get around America’s crippling import tariffs by importing a Panhard as part of his household articles. The car was confiscated by customs and auctioned off! American customs took no prisoners!

The denigrating of French derived machines continued in the American press. The Horseless Age reported, “Just as our machines are unable to compete against French machines in races on perfect highways so the French machines are unable to compete with American vehicles in endurance trials and on rough roads.” In reply, The Motorette Company complained to the press about their treatment, their French origins were becoming more of a hindrance than a help. An owner complained to the press about the lack of power on his 3 ½ horsepower Motorette and asked for help….was it the carburetor? Perhaps, it was more likely to be a timing problem for few understood the unique high tension ignition system. A system which was discarded by many contemporary owners in favor of the simpler solenoid operated trembler system – which made an assuring buzzing noise when working. More worrying was a May 7th 1901 order with deposit of $600 from a Mr. James Breeze for delivery in June. It was still not fulfilled by August, successful legal action followed.

All motor car manufacturers had problems at the time but the Motorette Company seemed to have had more than their fair share. A Mr. William Gemmel, a wealthy businessman who lived on Madison Avenue, had been on holiday in France and had hired a Panhard. He was impressed and decided to buy “French” on returning home and bought a De Dion. But he claimed it was unreliable and demanded his money back. A reporter from the New York Times followed up the story by door stepping Cornelius Field at his comfortable home in Dean Street, Brooklyn. Mr. Field said Mr. Gemmel had bought a second-hand machine that had had rough usage, which caused the breakdowns. Mr. Field said that the company had offered to build Mr. Gemmel another, which would be an improved version, no mention of court proceedings had been made. The court judged in Mr. Gemmel’s favor and seized two cars from the company’s New York Manhattan showrooms, to recover $2,400. At least four more suits followed for non-delivery and unreliability and by March 1902 the following year, $14,000 had been paid off in judgements. By then the company no longer held a manufacturing license, for in December Kenneth Skinner announced that he had cancelled his contract with the Motorette Company since they had failed to fulfil the conditions of their agreement. But it was not the end of the story.

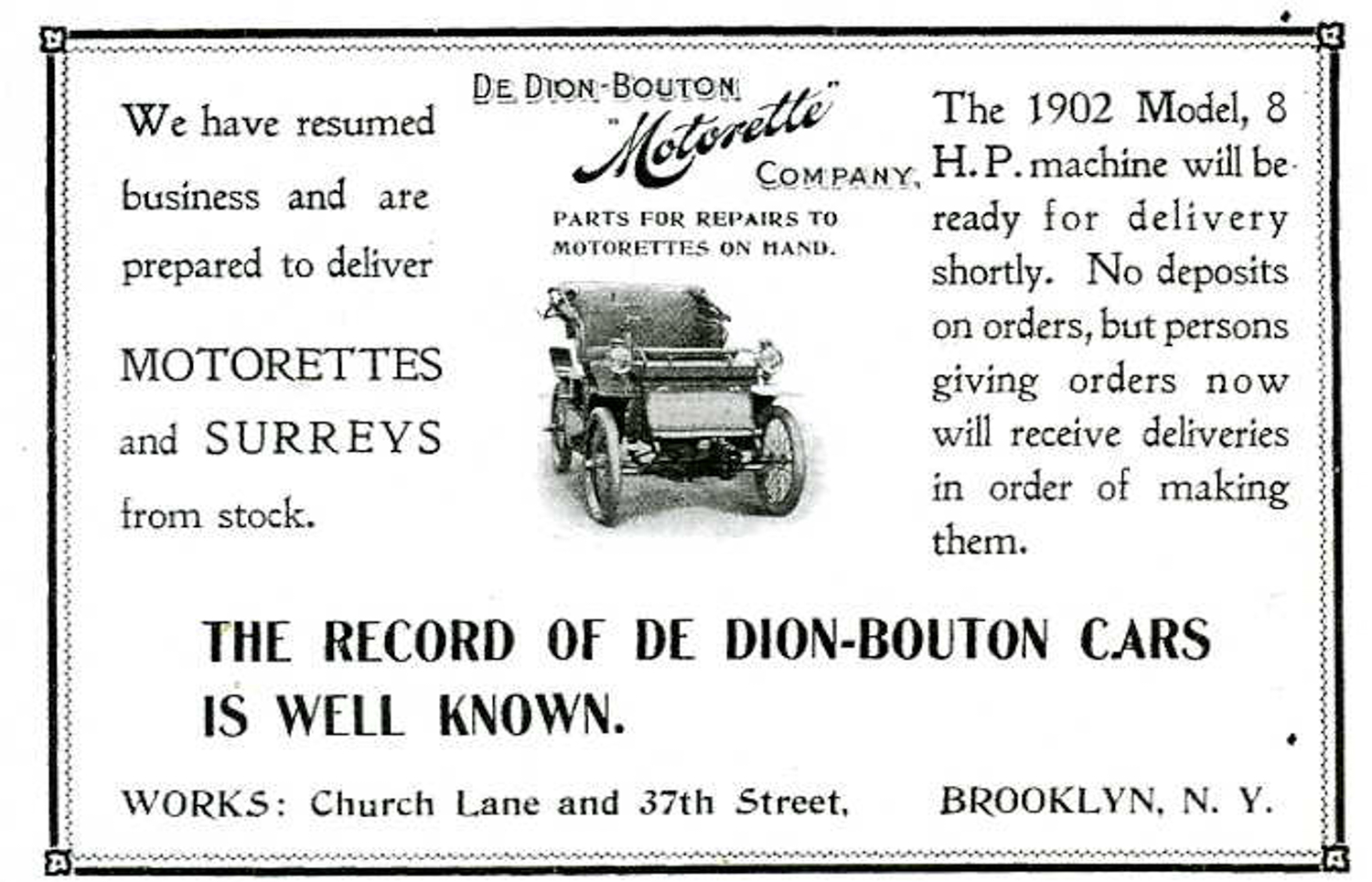

Histories of the De Dion Motorette Company conclude that it closed for business in Dec 1901, just over a year after production started. There were now 14,800 cars registered in America and perhaps 200 Motorettes built. Kenneth Skinner announced he would look for another company to exploit the patents in the U.S. or organize a company himself to do so. Two months later, Skinner announced to the press that he would be sailing to Paris to purchase De Dion spares and three cars of a new design. It was reported, “Should these prove as successful here as he anticipates he will immediately proceed to have them manufactured by some American firm.” In the same month another successful legal action was taken out against The Motorette Company by their Foundry for non-payment of $1039. But April saw Skinner reinstating The Motorette Company to manufacture cars, no doubt unable to find a replacement. And he also named the four American car manufacturers who used De Dion engines. Interestingly, one of the companies— George Pierce and Co —removed the De Dion lettering from their engines, no doubt unsure if its was advantageous.

In May, Mr. Skinner entered four cars into the Long Island Endurance Contest, helped by the fine roads, he gained first class awards and it was claimed he defeated all American and foreign machines of over double the power. Unfortunately, Mr. Skinner was then suspended from his Long Island Club for 3 months for exceeding the speed limit of 20 mph during the event. In the same month the original Motorette Company advertised it was back in business ready to deliver original Motorettes from stock from the original address. 40 of the original Motorettes and Surreys with 5hp and the new 6hp engine were available for immediate delivery – again any color or modification could be provided. Delivery of the new 8hp front-engined car was now also possible, but these were complete imported cars and with the “great demand from Europe only a limited number can be secured for the Unites States.” The Motorette Company continued to advertise – but only in the Horseless Age. The Automobile and Motor Review had sued the Motorette Company for $392, one assumes for non-payment of adverting copy! Kenneth Skinner now advertised dire warnings against using imported second-hand French and English engines in the ‘States for he would not supply parts for them. The reputation of the engines remained good.

In November 1902, Kenneth Skinner’s 8hp De Dion broke the time record for the run between New York and Boston. But this appeared as a “news” item; for no more paid advertisements appear in the motoring press for De Dion cars. In December 1902, it was recorded that Kenneth Skinner was to attend the Paris Motor Show, “He has arranged to bring the entire exhibit of the De Dion firm to this country for the Maddison Square Garden Show in January.” He did exhibit at the Show, in the basement. But there is no follow up in the motoring press. In July 1903, it was announced that Mr. Skinner, the U.S. De Dion agent, had produced a leaflet listing the new range of De Dion automobiles now available for import at $900 to $3500 tax paid. His enthusiasm for De Dion cars continued, in October 1903 the American Automobile magazine reported he had imported a unique De Dion car. This car had taken part 6 months earlier in the notorious Paris to Madrid road race which was stopped in mid race after 5 drivers (including Marcel Renault) and 3 spectators were killed. The car was used to good purpose in March 1904, when The Boston Evening Transcript reported it had broken the hill climbing speed record for the notorious Commonwealth Avenue Hill in Boston. This car still exists and still lives in the United States.

The De Dion did not fail entirely because of its great sophistication, its problem was that it was unsuited to the appalling condition of the roads in America. Its defect was its frailty and small size. American wagons and carriages were built with a standard 56” track but the French design had a 43” track! One side of the vehicle was always in the rough – except, perhaps, on Long Island’s well surfaced roads. The company had recognized that the Motorette had build problems, “many opportunities have been found to improve the original French design.” By 1904, Kenneth Skinner and the Motorette Company had disappeared from the pages of the motoring press. But Mr. Skinner still operated his garage in Boston and maintained his De Dion connections by selling genuine De Dion spark plugs. By then he was President of the Boston Automobile Dealers Association and a De Dion Motorette, could be picked up from a used auto dealer for just a few hundred dollars. One such machine was advertised with “improved ignition.” It had, like many others, been converted to the old technology of trembler coil ignition.

Count De Dion would not have approved!