Mercury— and the Ford Motor Company in general— was recovering from the economic recession of the late 1950s, along with the disastrously timed introduction of their new Edsel in 1958, and things didn’t really get better for the Mercury division until 1962 with the introduction of the new compact Comet.

In 1959, the Commuter was Mercury’s entry-level station wagon, positioned below the Voyager and the Colony Park, with its ersatz wood side panels and its 430-cubic inch V8, along with a plethora of accessories. Never the less, the Commuter was no loss leader, stripped down model.

Sal Orlando’s survivor two-door Commuter may be the best, and possibly the last, example of this model still in existence. It is not restored, but is an extraordinary barn find with a mere 34,346 miles on the odometer. And there is only a suggestion of a patina to emphasize its authenticity and originality. Photographer David Gooley ran across it, and its owner Sal, while in Monterey covering the Pebble Beach car show, and he arranged for us to see it.

Sal’s example of the marque is the exceedingly rare two-door, six-passenger version. But it has Mercury’s signature huge compound curve, turned back windshield and “hard top” pillarless side windows of the era, not to mention the distinctive sweeping pie slice taillights. These features make this big wagon look even longer and more luxurious.

Two-door station wagons in the ’50s were most commonly the least expensive utilitarian models, with the obvious exception of Chevrolet’s classic Nomad. Examples of what I am talking about are Chevrolet’s two-door Handyman and Ford’s Country Sedans of the ‘50s. But Mercury’s Commuter, which was the division’s entry level offering, is hardly a stripped down workhorse. It is bigger, more lavish, and much better appointed than any of the low-priced offerings.

I slide in on the clear plastic seat covers that were an extra-cost option, and make myself comfortable. There are acres of leg, head and shoulder room. The lounge sofa-like bench seat will easily accommodate three people comfortably. The shift lever was back on the steering column in 1959, after a couple of years of experimenting with push button shift, and I much prefer it to having to look down at little buttons while trying to drive.

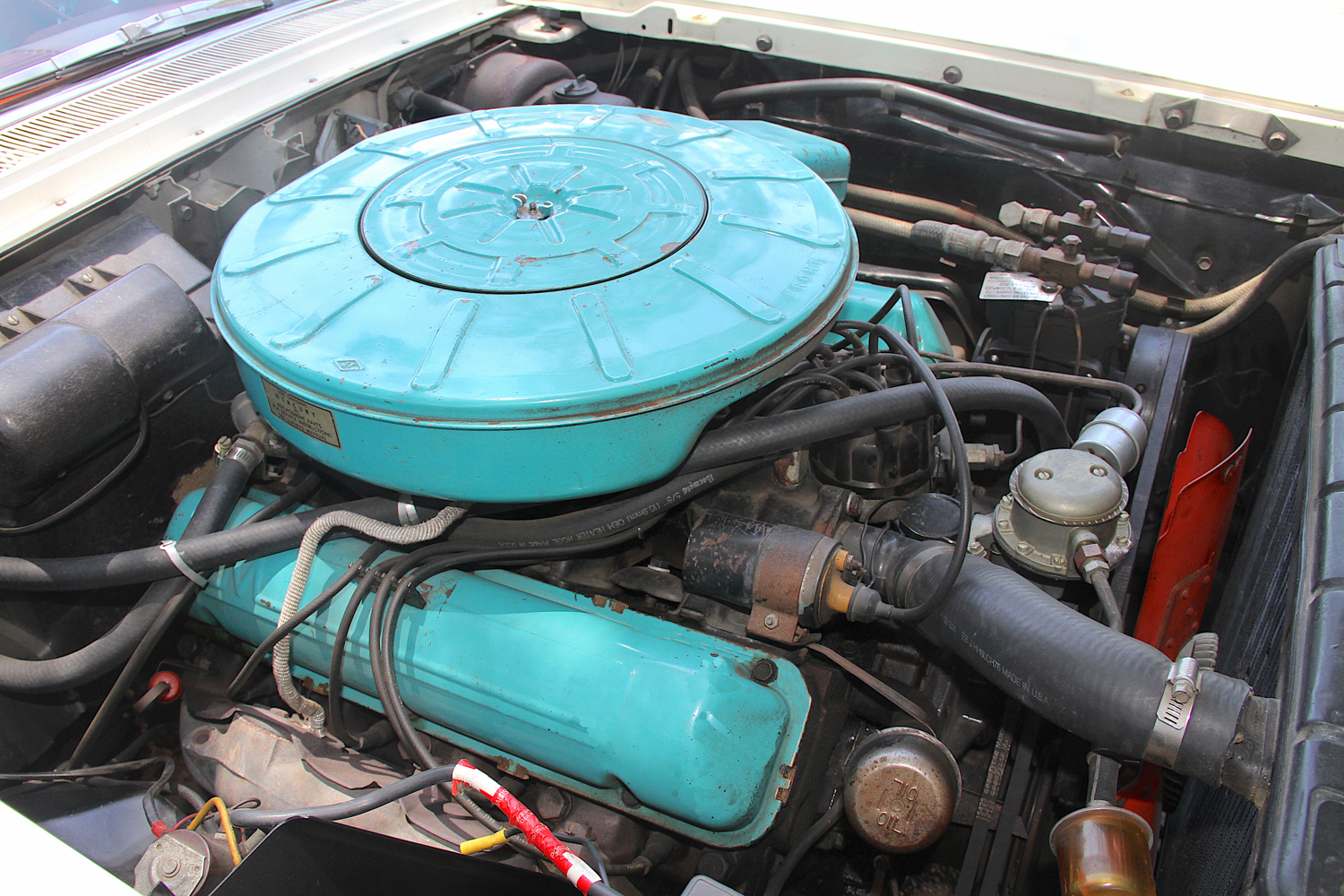

I pull the shift lever into neutral, as was required on the Ford automatic transmissions of the ’50s, and twist the key. The big Mercury Marauder V8 engine starts easily and settles into a gentle lope. The instrument panel is glitzy and busy, but easy to read, with a speedometer that has a big half-inch wide, foot-long red band that moves from left to right as you accelerate. The deluxe Town and Country AM push button radio is near at hand for the driver. And the air conditioning blows refreshingly cold, helping to keep my shirt from sticking to the plastic seat cover at my back.

The 383-cubic inch Marauder was the smallest member of the Mercury engine family. Produced from 1958 through 1960, it was only used in Mercury vehicles. It had a 4.30 inch × 3.30 inch bore and stroke. Output began at 312 and went to 330 horsepower, both using four-barrel carburetors. The 322 horsepower version was the only output for 1959, and power dropped to 280 horsepower for the final year of 1960.

I pull the shift lever into drive, which is actually second gear on a Merc-O-Matic, and my eyes are dazzled by the vast expanse of white hood. If I wanted to get away quickly, I could floor the gas pedal in Drive, which would shift the transmission into Low, but we are not in a hurry and we don’t have a hill to climb, so I just take off in Drive, which is actually second gear.

We ease away at a gentle pace, and the expression “land yacht” comes to mind. The ride is very cushy and softly sprung, and the steering nearly effortless. The big Merc wagon swings around slowly and majestically with a bit of body lean, and then we are on our way. The transmission shifts somewhat abruptly, and we are up to speed quickly and almost imperceptibly. Acceleration in this car is similar to watching a 747 take off. The plane is in fact doing 160 miles per hour at lift off, but because of its size it looks as if it is doing 30 miles an hour.

Six passengers would be quite comfortable in this large well-appointed cabin, with its two tone red and gray upholstery and almost no center drive line tunnel. And you still have room for eight large bags of garden mulch and a golden retriever in the huge cargo compartment behind the seats.

Ironically, by 1959, the Station Wagon moniker was so anachronistic as to be almost meaningless. That’s because originally a station wagon was just that. A horse-drawn wagon used to pick up people at the train station and take them to their hotel. Later, when the automobile came along, a few motorized station wagons were built, mostly out of oak, ash, maple and mahogany. The Star division of Durant Motors was the first to offer such a vehicle from the factory in 1923. Wood bodied station wagons were initially utilitarian, purpose-built vehicles, but they were also quite handsome, and they turned out to be practical for ranchers and suburbanites as well.

This led to a great profusion of woody wagons offered by nearly every automaker by the late 1930s and ’40s. In fact, the look and style of the woody was so popular that it was also applied to cars, such as the Chrysler Town and Country convertible coupe, as well as Ford and Mercury Sportsman convertibles. Even some Chevrolet coupes got a few wood panels stuck on their doors. But by that time, the wood was no longer structural but ornamental.

However, all that beautiful wood had its downside. It required a great deal of maintenance to keep it looking fresh, including sanding and varnishing every six months in regular use. Also, wood absorbed water and swelled when wet, and dried out and shrank and creaked in dry weather. And for the manufacturers, wood bodywork was intricate, labor intensive and heavy.

Chevrolet debuted the first all metal station wagon of sorts with its 1937 Suburban. It was big and entirely utilitarian and was built on a truck chassis, but it captured the market for a no-nonsense people and cargo carrier. The new Suburban could transport eight people in reasonable comfort, in a sturdy low maintenance all steel vehicle. It sold initially for $685 and was a great success, and is to this day.

However, Chevrolet didn’t own the name Suburban, and it soon became the generic term for that type of vehicle from then on. And then, in 1949, Plymouth came out with the first all steel station wagon on a car chassis and also called it the Suburban. That began the trend away from Woodies. Of course, even to this day there are a few cars made with fake wood, Di-Noc decals on their bodywork to carry on the old woody look.

Ford debuted the Mercury in 1939 as a mid-priced offering, positioned between the Ford and the Lincoln Zephyr, as they phased out the high-end, hand-built K series luxury cars. Cadillac and Packard jettisoned their big 12 and 16-cylinder luxury car as well, and went over to mass production completely as part of an industry trend.

The new Mercury for 1939 and ’40 had its own body and styling, but in 1941 Ford and Mercury shared most body panels. Also, the four-door convertible sedan was dropped from the Mercury line that year, and a woody wagon was added, using the same wood body as the Ford from the cowl on back. All of the company’s station wagon bodies were built at Ford’s Iron Mountain Michigan plant using birch framing and maple or gum paneling harvested from the local forests that Ford owned.

And then, in 1949, Ford redesigned and modernized all of their offerings, although they stayed with their tried and true flathead engines at a time when Cadillac, Oldsmobile, Studebaker and Chrysler were going to more modern overhead valve configurations. Mercury was given the Lincoln chassis at that point, and shared some body panels with it. The result of these changes was a huge sales success for the entire line, with the ’49 – ’51 Mercury doing exceedingly well.

After World War II, the new Mercury was the cool car to have. It was good looking; a pretty hot performer, and the customizers such as George Barris made it iconic to young people. In fact, they were arguably the most popular Mercs ever. And the big Mercury wagons did well too, as they transitioned to Di Noc decals on all metal bodies along with the rest of the industry.

The need for actual station wagons was largely a thing of the past by the early ’50s, but a new and greater marketing niche more than made up for it. That’s because after World War II huge numbers of people moved out of the cities and into the fresh air and sunshine of the suburbs. Returning G.I.s after the war qualified for low interest FHA loans, and this led to a building boom of mass-produced housing for a tsunami of new baby boomers.

People wanted more than just a place to live as well. They wanted gardens, lawns and a little of the countryside that many of them had come from before the war. Also, the government wanted the population more spread out, because the cold war was on and nuclear war was not unimaginable.

Some of the new housing developments of the era even offered backyard bomb shelters as an extra cost option. And once a month in elementary school we had drop drills in case of attack. While the rest of us huddled under our desks, one designated boy would voluntarily sacrifice himself by lowering the blinds to prevent showers of glass.

Also, when President Eisenhower’s interstate highway system came in during the mid-’50s, it was a requirement that there be straight stretches at regular intervals long enough to allow jet aircraft to use it as runways in an emergency. This all sounds macabre today, but it was quite real during the era of such movies as “Doctor Strangelove” and “On The Beach.” At the time they were much more frightening.

Another thing that made the 1950s a golden era for the evolving station wagon was that nobody flew anywhere unless they were wealthy. Few took the train by that time either. It was a time of family vacations in which everybody loaded up their station wagons with camping gear, canoes and fishing tackle, and set off to tour the country on the new highway system. The camper mounted on the pickup truck and the camper van came later in the ’60s.

Back to today, as we are cruising the golden hills around Santa Cruz, Sal Orlando says: “This car is a real ‘Little old lady story.’ My neighbor, Marie, was the original owner of my wagon, and she was a schoolteacher working in China Lake, California, when she bought the car. Its base price was $3,145 dollars, so it was not an inexpensive car.” This was more than the contemporary Buick equivalent at $3,025.

“When Marie moved to San Jose, California, she realized that the car was just too big for driving around town. One day she drove it into her garage and vowed, ‘to never drive it again.’ After 20 years of trying to buy it from her, she finally sold the car to me on July 22, 1995. Turns out it was built in Los Angeles, on January 20, 1959.”

In the 1960s, Mercury wagons got even bigger, even though the company’s recovery rebounded to sales success largely thanks to the new compact Comets. The compacts made big sales inroads for the industry in general, as did foreign cars such as the VW Kombi bus with the younger generation. But the big cars just kept getting bigger and by 1969 the Mercury wagon was nine inches longer.

Sal has taken exceptional care of the car ever since, and it shows. It would not take a trophy at a prestigious show unless it was for original cars, but it could win that category handily, even though it is a single tone white car from an era when two-tone paint schemes were almost the norm and it also only had the smaller dog dish hubcaps and not the more expensive full disk types on the Colony Park models.

It was the Oil Crisis of 1973 that started the downward spiral for the big station wagon tailgate party. Gasoline shot up 300 percent, and people started buying smaller more economical cars in droves. But the station wagon evolved again into a new species. That’s because it was the ancestor of the Plymouth Voyager minivan in 1983. That set off a round of new hatchback vehicles that in turn evolved into the so-called SUVs we have today.

Sadly, Mercury did not survive the transition and went under in 2011, even though the Mercury Grand Marquis was an outstanding automobile. In fact today, the Sport Utility Vehicle is a big part of why, in 2020, Ford decided it would no longer sell sedans in the United States.

The sun is starting to set behind the golden hills of central California, and our cruise in Sal Orlando’s 1959 Mercury Commuter station wagon is coming to an end. If you have not driven or ridden in a big luxurious American car like this one from the golden age of the station wagon for a long time, you would be in for a treat given the chance. We enjoyed our journey back in time, but now we must head home in my humble modern sedan. It is a little like going from first class back to economy on an airliner.

SPECIFICATIONS

| Length | 218.6 inches |

| Width | 80.7 inches |

| Height | 57.8 inches |

| Wheelbase | 126 Inches |

| Fuel capacity | 20.1 gallons |

| Production | 148,946 Five-door |

| 1,051 Three-door | |

| Horsepower | 322 |

| Torque | 409-ft.lbs. @2,900 rpm |

| Transmission | Merc-O-Matic automatic |

| Acceleration | 0-60 mph in 10 seconds |

| Quarter mile 17.7 seconds |

ACCESSORIES

- Air conditioner with heater ($385).

- Backup lights ($8.90).

- Clear plastic seat covers ($29.95).

- Courtesy light group ($9.30 Monterey).

- Dual exhausts ($25.80).

- Electric clock in Monterey and Commuter ($14.20).

- Heater and defroster ($71.15).

- Heater and defroster with Climate Control ($84.95).

- Lower back panel reflector ($10.90).

- Optional Monterey trim ($30.60).

- Outside rear view mirror ($6.95).

- Padded dash in Monterey and Commuter ($17.10).

- Power brakes ($34.55).

- Power seat, Four-Way ($60.40).

- Power seat, Seat-O-Matic ($82.20).

- Power steering ($83.50).

- Power tailgate window, Commuter Wagon ($26.80).

- Power windows ($84.50).

- Radio, Signal-seeking ($90.25).

- Radio, Push button ($68.75).

- Rear seat radio speaker ($9.30).

- Safety speed monitor ($12).

- Seat belts ($12.25 each).

- Third seat for station wagons ($90.70).

- Tinted glass ($34.90).

- Tinted windshield ($19.79).

- Two-tone paint ($14.25).

- Undercoating ($15).

- Whitewall tires ($32.95).

- Windshield washer ($11.75).