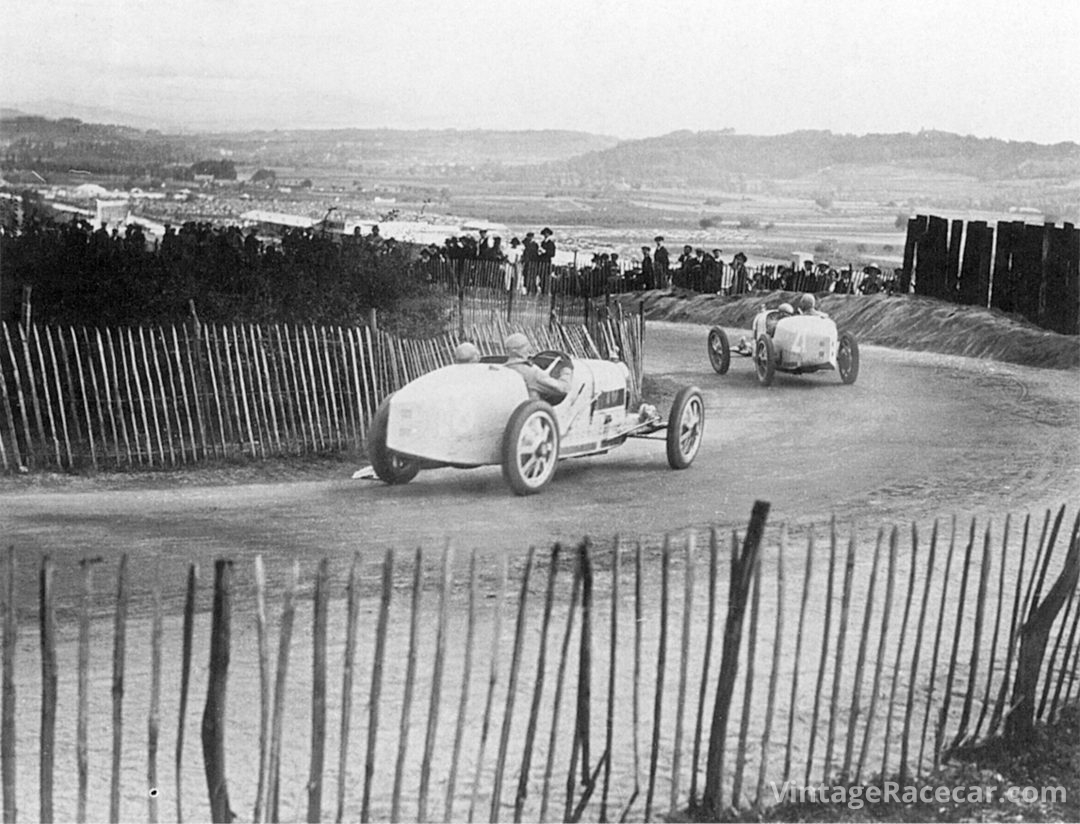

Not for the first time, one of motor sport’s most successful cars was a huge flop when it made its debut. In this case, it was the Bugatti Tipo 35, six of which were driven on the public roads from Molsheim to Lyons in late July 1924, to compete in the Grand Prix of France.

Ettore Bugatti, who personally drove one of the cars to the race, didn’t do things by halves. Three railway wagons and two draw-bar trailer trucks humped the team’s spares, equipment, personnel, and creature comforts to the Rhône region’s capital city for the race. When they got there, the Bugatti family “made do” with a super-luxury caravan; and the 45 drivers, mechanics, and other staff lived in a well-appointed tent with beds for all, bathing facilities, toilets, a kitchen, and even an ice-box.

The T35s made a great impression on the thousands who turned up for the Grand Prix. The cars were smaller and much more refined looking than people were used to seeing. They looked like single, all-encompassing entities rather than their older brethren, which seemed to be a chassis on wheels with various “boxes”—engine, cockpit, fuel tank—almost haphazardly strewn along their length. The Bugattis’ crowning glory was, of course, their powder-blue color, which bathed the cars in a hue it was hard to dislike—especially for the French!

But only two 35s finished the race: Jean Chassagne came in 7th and Mlle Renée Friderich 8th in the cars. The rest fell by the wayside, mainly because their tailor-made tires were not vulcanized properly, so the treads separated from the carcasses.

An inauspicious start for a car that became an icon, one that has been revered for the best part of a century for its achievements and consummate beauty. In its various forms, the Tipo 35 would eventually turn Bugatti into the 1926 World Champion Grand Prix racing constructor and win literally thousands of races—more than 30 of them top international Grands Prix, five consecutive Targa Florios plus three Coppa Florios—dominating motor sport most of its competitive life. And when that was coming to an end, the T35 was born again as the Tipo 51, essentially a 35 with twin overhead camshafts, and that car kept winning and taking top places in the upper echelons of the sport right through to the end of 1933.

About 345 Tipo 35s and around 40 T51s were built in almost a decade during the Twenties and Thirties. The T35 that flopped in the 1924 French GP was powered by a straight eight-cylinder, 1991–cc sculpture of an engine. The 2292–cc 35T was built in the spring of 1926 for the rigors of the Targa Florio. The 35C of 1927 was a supercharged 1991–cc car and the T35B of the same year a supercharged 2292–cc. The Tipo A, called the “Race Imitation 35” at the factory, was a less expensive version of the car. It had headlights, wings, windscreen, and hood and won many voiturette races.

The T35’s elegant “horseshoe” radiator with its renowned EB badge made the car look narrower than it really was: It fronted a groundbreaking design of seamless beauty created as a cohesive unit of great refinement that has been an object of adulation and desire right through to the present day.

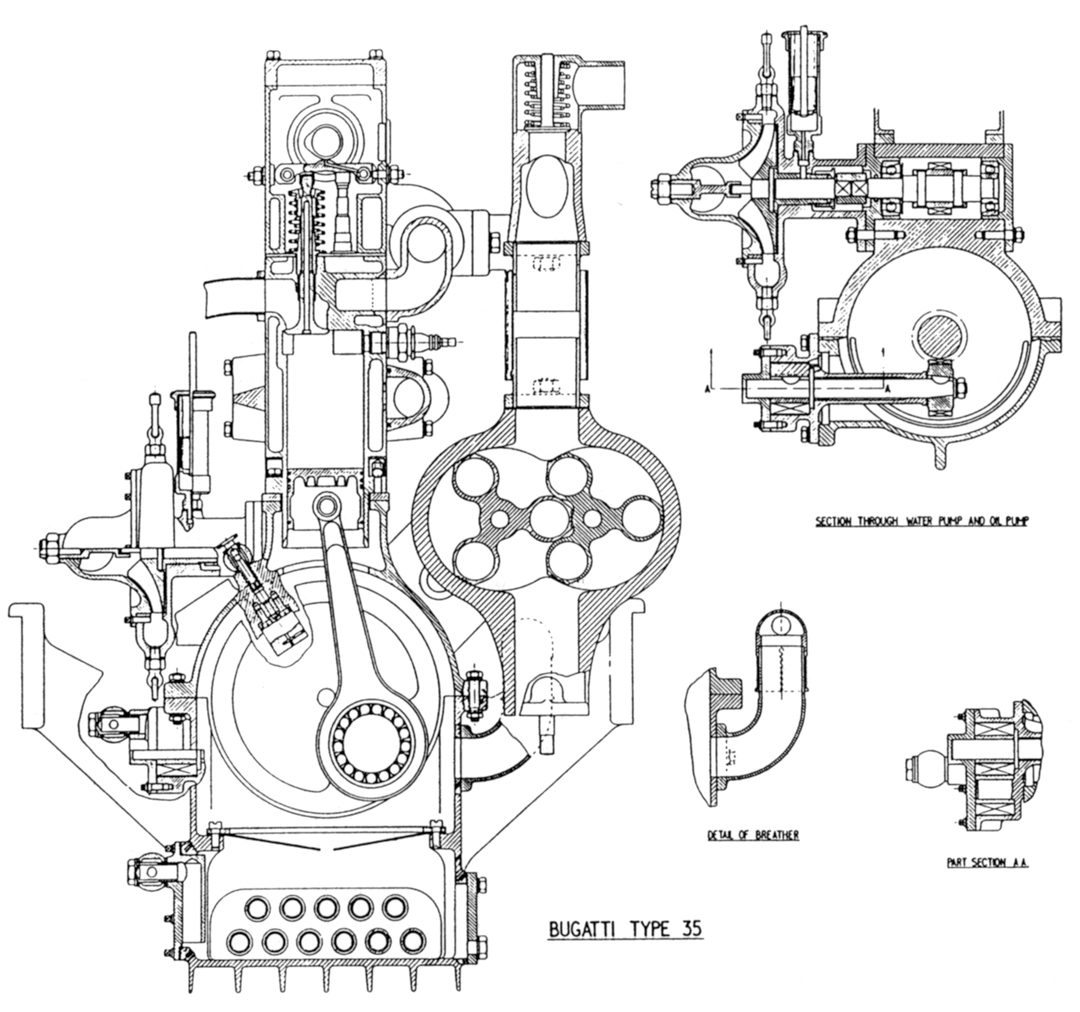

The car had a track of 3 ft 11.5 ins and a wheelbase of 7 ft 10.5 ins. The engine was secured to the frame at four points; the separate gearbox was fixed to two robust tubes that ran from one rail to the other and contributed to the chassis’ rigidity, as did the bulkhead. The frame and springs were swept inward at the rear in the shape of the body. Front suspension was not independent, but comprised semi-elliptical springs outside the frame. The front axle was hollow in the center and solid at both ends, a gem of the forger’s trade. The rear boasted two, reversed, quarter-elliptic springs fitted obliquely under the chassis. As well as the way the springs and dampers were deployed, rear axle control was by tubular torque rods anchored to the axle housings’ ends and to the outside of the chassis rails with bronze manacles and a pressed steel torque arm running from the back axle housing to the gearbox. There were Bugatti-designed friction-type dampers at the front and rear and magnificent, spoked light alloy wheels with brake drums, except for the A with its conventional spoked wheels.

Photo: Steve Oom

The T35s engine had nondetachable cylinder heads made of two blind-end blocks each of four cylinders, three valves per pot (2 inlet and 1 outlet), a single overhead camshaft, magneto ignition (coil on the A) driven from the back of the camshaft with an advance that could be adjusted by a dashboard lever, water-cooling by pump without a fan, wet multi-plate clutch, and an outside gear lever. The five variants’ estimated power output and top speed were 70 hp and 87 mph for the A, 90 hp and 105 mph for the 35, 100 hp and 106 mph for the T, 100 hp and 120 mph for the C, and 110 hp and 135 mph for the T51.

They weren’t the fastest cars of their day because, unlike much of the opposition, Ettore Bugatti had initially refused to supercharge his cars. They were powerful, yes, but other competitors had a higher top-speed capability. In divine compensation, the T35s did have outstanding roadholding, were highly maneuverable and easy to drive. A T35 didn’t just have an engine and chassis cohabiting in some uneasy marriage, but was a silken blend of components designed to act as one.

Today, though, it is nigh on impossible to find a T35 which is 100 percent original. Most were damaged in races and repaired to varying degrees of quality and many have been modified by generations of owners and mechanics. Cars that are 50 to 70 percent original command big money today.

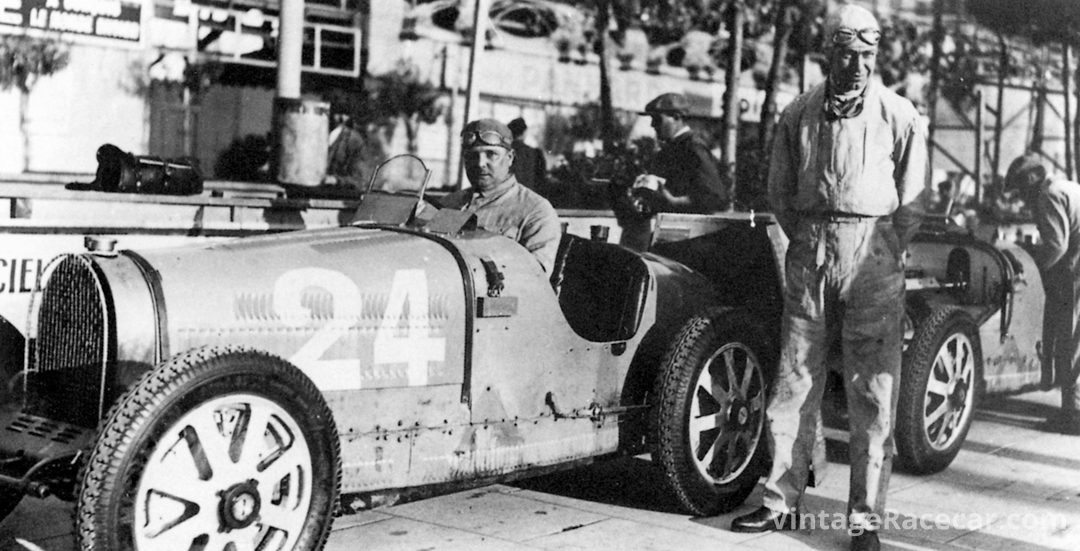

Of course, the list of men—and women—who raced the Bugatti T35 and 51 reads like a Who’s Who of the period’s motor racing. They included Robert Benoist, Pietro Bordino, Georges Bouriano, Guy Bouriat, Gastone Brilli-Peri, Antonio Brivio, Malcolm Campbell, Louis Chiron, Caberto Conelli, Bartolomeo (Meo) Costantini, Stanislav Czaykowski, brothers Ferdinand and Pierre de Vizcaya, Albert Divo, René Dreyfus, Philippe Etancelin, George Eyston, Madame Renée Friderich, Jules Goux, Earl Howe, Madame Elisabeth Junek, Marcel Lehoux, Giulio Masetti, Emilio Materassi, Ferdinando Minoia, Guy Moll, Tazio Nuvolari, Miss Kay Petre, Mrs. Lucy Schell (Harry’s mother), Louis Trintignant (Maurice’s elder brother) Achille Varzi, Pierre Veyron, Heinrich-Joachim von Morgen, William Grover-Williams Jean-Pierre Wimille, Goffredo Zehender, and Hermann zu Leiningen.

Bugatti Grand Prix and double Targa Florio winner Meo Costantini so enjoyed working for Molsheim that he did so for nothing but the sheer enjoyment of it all. He was eventually put in charge of the company’s racing department. The de Vizcaya brothers were the sons of a prominent French banker, who helped Ettore Bugatti to start his remarkable business.

When a legendary car has won as much as the Bugatti T35 and 51, it is difficult to choose a couple of highlights from a landslide of stunning performances for an article such as this. So I have gone for two totally different chunks of the sport, in which the T-cars from Molsheim virtually obliterated the opposition: Top international Grand Prix motor racing from mid-1924 until the end of 1933, in which the Bugattis often took all top six places, and the Targa Florio, which they won nonstop for half a decade.

But back to the beginning and 1924, when Grand Prix cars’ maximum engine capacity was still 2000–cc and their minimum weight 600 kg. With the Lyons flop behind them, the T35s’ next big race was the Grand Prix of San Sebastian at Lasarte six weeks later, for which they were fitted with properly “cooked” tires. The T-cars were up against stiff opposition from the Delages of Alberto Divo, André Morel, Robert Benoist and René Thomas, the Henry Segrave and Lee Guinness Sunbeams, a couple of Mercedes-Benz driven by Giulio Masetti and Max Seiler, two Schmids with Jules Goux and Giulio Foresti at their wheels and Alfieri Maserati in a much modified Diatto that many described, tongue-in-cheek, as the first Maserati. Despite a leaking radiator hose and the need to call in at the pits several times for more water, Meo Costantini kept going at a furious pace to come second to Henry Segrave’s Sunbeam, with Pierre de Vizcaya and Jean Chassagne 5th and 6th despite ignition problems.

The cars won none of the big Grands Prix in 1925, but Masetti did take the lesser GP of Rome in a T35, and Costantini the Tourist GP at Montlhéry, in which Pierre de Vizcaya came 2nd. But the Bugattis disappointed in the Grand Prix of France at the Paris circuit, where Costantini, Jules Goux, and Ferdinand de Vizcaya finished a lowly 4th, 5th and 6th.

It was in 1926, with new rules dictating a 1500–cc maximum engine capacity and a minimum weight of 700 kg, that the T35s first blew motor racing apart. It happened at the year’s Spanish Grand Prix at Lasarte on July 25. Only the Robert Benoist/Louis Wagner Delage 2LCV, which came 3rd, prevented Ettore’s team from taking all the top six places, with victory going to Costantini by a staggering 16 mins 13 secs over his teammate Goux. That performance and victories by Goux in the Grands Prix of France at Miramas and Europe at Lasarte plus the win by Jean Charaval, who raced under the nom de plume Sapiba, in the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, secured the 1926 Grand Prix World Championship for the Alsace team.

The following year belonged to Delage, for whom the great Robert Benoist won four out of the championship’s five races in the constructor’s 15S8s. For the next four years after that, however, nobody else stood a chance. The Tipos 35 and 51 cleaned up.

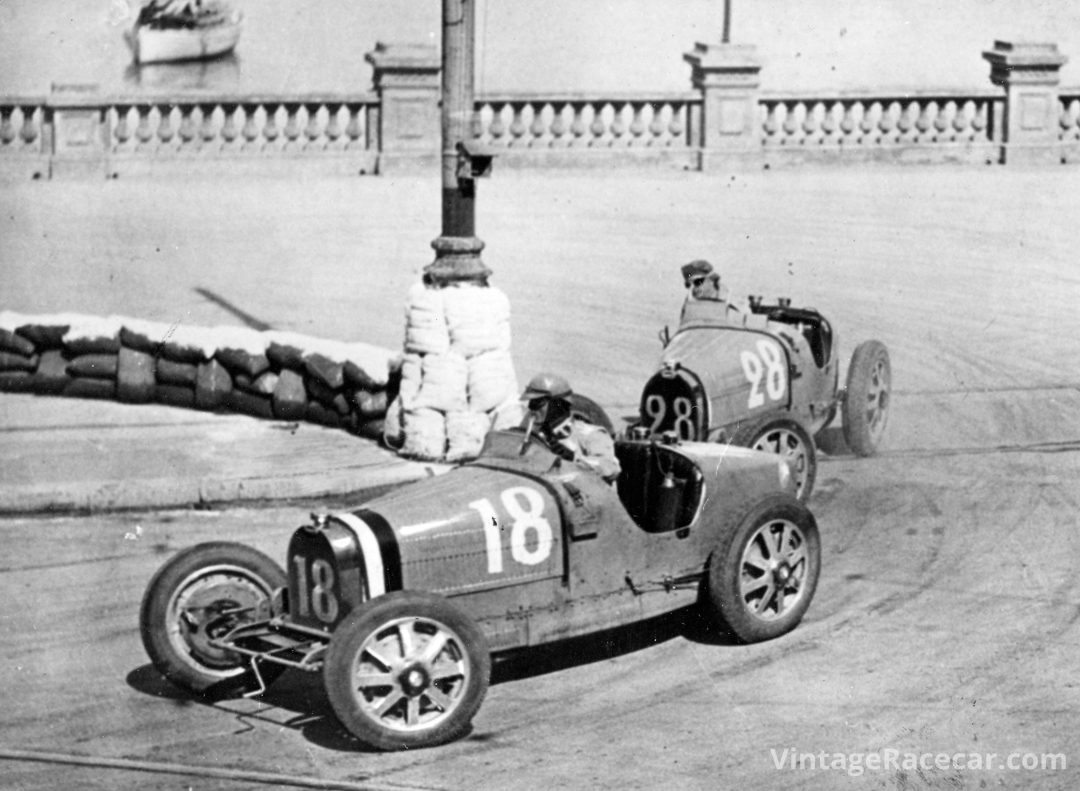

French-born William Grover-Williams of English parentage, who raced under the name W. Williams, won the 1928 Grand Prix of France in a T35C. That year, the ACF’s hardy annual was a 10-lap sports car handicap event of the 16.156-mile Comminges circuit at St. Gaudens, in the shadow of the Pyrenees. Williams’s supercharged Tipo 35C covered the 161.560 miles at an average of 65.639 mph and put up a fastest lap of 10 mins 48 secs to beat a mixed bag of two Salmsons, a Stutz, a Lombard, and a Chrysler. Rudolf Caracciola and Christian Werner took the Grand Prix of Germany, the season’s other sports car race, in one of the big six-cylinder Mercedes-Benz SSs; but the T35C came back with a vengeance 10 days later, when Monaco’s Louis Chiron began a remarkable four-year roll in Bugattis by winning the Grand Prix of San Sebastian at Lasarte. In fact, the Molsheim cars took all six top places, Chiron the win, Robert Benoist came 2nd in a T35B, Algerian gentleman driver Marcel Lehoux 3rd in another T35C, Italian Goffredo Zehender 4th in a T37A, Manuel Blancas 5th in a 35B and “Torres” 6th in the second T37A.

A minimum weight of 900 kg and the use of commercial fuel were the new rules for 1929, when the Bugattis won four out of the top five Grands Prix. It began with a stunning display of class and a preview of what was to come when Grover-Williams won the first ever Grand Prix of Monaco in his Bugatti T35B after a monster battle with Rudolf Caracciola in the big, heavy Mercedes-Benz SSK. The unwieldy Merc was too much of a handful for the German hero on the tiny, twisting Monte Carlo city circuit—1.976 miles long compared to the 11.029 miles of Lasarte and 17.563 miles of the Nürburgring—and he eventually came home 3rd. All the other top-six placings went to Bugattis—2nd was Georges Bouriano in a 35C, 4th Georges Philippe in another C, 5th Renée Dreyfus in a 37A, and 6th Philippe Etancelin in his Bugatti T35C.

Just over six weeks later, Williams was first across the finish line in the French GP in his T35B. Then Chiron won the German in a T35C and the Spanish in a B. Achille Varzi was the only interloper; he won the Grand Prix of Italy in an Alfa Romeo P2. In 1930, Bugatti won four out of a possible six international GPs. René Dreyfus took Monaco in a T35B, Louis Chiron the Belgian GP in a C, Philippe Etancelin the French in another C, and Hermann zu Leinigen/Joachim von Morgen the Czech at Brno in a 35B. In those two years alone, Bugatti 35s won 8 out of a possible 11 international Grands Prix, set the fastest lap at 7 of them, and took 38 top-six places out of 66.

The twin overhead camshaft Bugatti Tipo 51 took over in 1931 where the less powerful T35 left off, a year in which Bugattis won four out of the five top Grands Prix again. Louis Chiron drove a 51 to its debut victory in his hometown Grand Prix of Monaco at Monte Carlo, and he and Achille Varzi won the French GP in the car. In the Grand Prix of Belgium, Williams and Caberto Conelli in a 51 trounced a powerful lineup of Alfas and Mercedes driven by the likes of Nuvolari, Borzacchini, and Birkin; then Louis Chiron did likewise with the car in the Czech GP.

In 1932, the 51 bubbled away under the surface without much success, but Achille Varzi gave the car its swan-song victory in the 1933 Monaco Grand Prix. After that, the T51 was subdued by the new Alfa Romeo Tipo B P3, the Maserati brothers’ 8CM, and the withering Auto Union/Mercedes-Benz onslaught.

While all this was going on, Molsheim themselves organized and ran the Bugatti Grand Prix, which was held on the Le Mans circuit from 1928–1930. These events were run for privately owned Bugattis, which were given no works support. Their steamroller rules evened out the races so that all Bugatti entrants stood a chance. A brand-spanking-new Tipo 35 was the top prize in 1928, and went to Tipo 37 driver André Dubonnet. Juan Zanelli drove a Tipo 35 to victory in 1929 and 1930 and won himself T43s for his trouble.

What was the secret of the T 35’s amazing success on both the more car-friendly Grand Prix circuits of the period and the goat tracks of Sicily? The answer is Ettore Bugatti’s famed philosophy that his racing and road cars should be as compatible as possible, so that they were a blend of the flexibility and tractability of a reliable touring car, but had the performance, roadholding, and reactions of a track racer. The T35s suited the narrow, earthen tracks of the Targa Florio like no other car of its day. It was glorified by an unbeatable combination of good low-speed torque, outstanding handling, exceptional reliability, and excellent brakes; just the ticket for the 6,000 hairpins of the 336-mile, five-lap race through the Madonie Mountains.

There were only 15 starters for the 1925 Targa Florio, yet the main contenders were both French: four 4000–cc Peugeot 174 Ss driven by André Boillot—the 1919 winner—Louis Wagner, Christian Dauvergne, and Louis Regal, and three two-liter Bugatti T35s in the hands of Meo Costantini, Pierre and Ferdinand de Vizcaya. The rest included an OM 665 S driven by Renato Balestrero, Guido Ginaldi in an Alfa Romeo RLS, two Tatra 11s for Fritz Huckle and Karl Spooner, and a Fiat 501 S driven by Giuseppe Pio.

Things did not look good for the factory Bugattis at the end of lap one. Boillot was in the lead followed by Wagner and Dauvergne with Costantini in 4th, but then the Peugeot assault began to fall apart. Boillot slowed with tire trouble. Dauvergne went too fast into one of those hairpins, hit the verge, his car overturned, and he was trapped inside the burning Peugeot before being rescued. Wagner stopped to help save Christian, which cost him time, and Rigal retired after an accident, so the Bugattis took over. The two remaining Peugeots did fight back, but they were unable to catch Costantini, who won in 7 hrs 32 mins 27 secs at an average speed of 44.5 mph. Louis Wagner came 2nd, almost five minutes behind him, and Boillot kept going to take 3rd, eight minutes down on the winner.

A slew of Bugattis were entered for the 1926 Targa. Molsheim sent more powerful 2.3-liter T35Ts (T for Targa) to Sicily for Costantini, Ferdinando Minoia, Jules Goux, and André Dubonnet, who were backed by seven 1.5-liter Bugatti 37s and 39s. There should have been stiffer opposition from the 34 starters. They included four big 2-liter, 12-cylinder Delage 2 LCVs being driven by Robert Benoist, 1921 and 1922 Targa winner Giulio Masetti, Albert Divo, and René Thomas, and making its debut was the first ever Maserati, the 26 being campaigned by its designer Alfieri Maserati, who was really there to try out the new car under racing conditions.

As in 1925, the race was over five laps of the Medium Madonie Circuit for a total distance of 336 miles. The major disappointment was the poor performance of the potent Delages. Oodles of power and bulk were never an advantage on the Targa loose surfaced “roads,” so the Grand Prix winners turned out to be uncharacteristically slow in acceleration and awkward to handle under braking. On top of that, Giulio Masetti’s car seemed to pull to the left all the time and nobody could work out why. Two-thirds into the race, his car went into the first of two corners before the Sclafani Bridge but, going into the second bend, the Italian’s car suddenly lurched to the left, reared up, and overturned. The driver was still pinned under the Delage when his teammate René Thomas stopped to help, but Masetti died within minutes of the Frenchman’s arrival. The three sister cars were withdrawn from the Targa as a mark of respect for the popular Italian.

That left Costantini, Minoia, and Goux in the top three places, which they retained until the end, confirming the factory Bugattis’ total domination of the race. The team also won the magnificent Coppa Florio challenge trophy.

Alfieri Maserati and his 26 kept going, came 8th and won the 1101-1500–cc class, a very satisfactory shakedown test!

Bugatti’s own version of the Roots supercharger was first used in Grand Prix racing. The two-liter was given the blower and became the T35C, three of which were entered for the 1927 Targa Florio. As a result, the cars’ top power output increased by another third from 90 hp to 120 hp, which served works drivers Emilio Materassi, Fernando Minoia, and André Dubonnet well; but they were not the only supercharged Bugattis in the event. Molsheim sometimes sold off its unwanted racing cars to privateers, and one of them was an experimental 2.3-liter T35B with a larger supercharger than the Tipo C. It was bought by Prague banker Vincent Junek for his talented, 26-year-old wife Elisabeth. Wearing her habitual racing gear of a white blouson, blue skirt, and white leather helmet, Elisabeth was much admired by many of the male drivers, but she would have no truck with their amorous advances, since her codriver was her husband.

The 22 starters also included two Maserati 26s, one for the car’s designer Alfieri and the other for one of the men who invented the Mille Miglia, Aymo Maggi. André Boillot was back again with a Peugeot 174, and two 1.1-liter Salmsons were driven by up-and-coming stars Mario Umberto (Baconin) Borzacchini and Luigi Fagioli.

It was not so much a question of if a Bugatti would win, but more of which one would take the laurels. On the first lap, there was a fevered crossing of swords between the two front runners Boillot and Dubonnet, but that subsided as the two men realized there was still a long way to go and their machinery would collapse under the strain if they kept up that pace. Eventually, Minoia took the lead with his blower power as Elisabeth Junek gamely held 4th. She was lucky to get away with superficial injuries when the principal gear in her car’s steering box broke and she crashed into a wall and out of the race.

Materassi eased his way into the lead and set the fastest lap of 46.938 mph on his way to winning the race, with Caberto Conelli 2nd in a supercharged 37A and Alfieri Maserati 3rd in his 26 B.

There were no fewer than 29 Bugattis among the 36 starters in the 1928 Targa Florio, and this time Ettore sent four factory cars to Sicily: a 35B for Albert Divo, two-liter 35Cs for Giulio Foresti and Louis Chiron, and a supercharged 37A for Fernando Minoia. Elisabeth and Vincent Junek were back with their 2.3-liter blower T35B and this time they would give the professionals a real run for their money. Chiron took an early lead, followed by a hard-charging Giuseppe Campari in an Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 SS and a rather piqued Divo.

No matter what Albert tried, he could not shake Junek, who was always in his mirrors. Chiron lost time changing a flat tire and that put Campari in command, while Elisabeth overtook the Monegasque and gave chase to Divo once more. She eventually passed the edgy Frenchman and set off after race leader Campari. Amazingly, this fragile-looking young woman slipped by the great Italian to lead the punishing Targa Florio and build up a 20-second advantage over the Alfa. But, egged on by his pits, Campari pushed harder, made up his deficit, and passed the young girl. She was beginning to tire, and lost time when she muffed one of the thousands of hairpins, which helped Divo close in on her.

Although race weary, Elisabeth still pushed hard and reduced the two minutes between her and leader Campari to one, but with Divo pressing her hard one of her tires punctured. Vincent took two minutes to change the wheel and that lost them a very real chance of victory. Instead, Albert gained ground on Campari, overtook him and won the race—plus the Coppa Florio—for Bugatti. Remarkably, an exhausted Elisabeth Junek still came 5th and was regarded by many as the moral winner of the race.

Next year, after an almighty battle with Gastone Brilli-Peri’s Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 SS, Albert Divo won Bugatti’s fifth consecutive Targa and third Coppa Florio in a Tipo 35C. Fernando Minoia drove the message home with a convincing 2nd place.

By this time, however, the vultures were already circling. The Italians had had enough of the French winning their great race. Although Divo, Chiron, Conelli, and Williams all had supercharged eight-cylinder Bugatti 2300s for the 1930 Targa, they were unable to defeat the surgical brilliance of the stylish Achille Varzi in an Alfa Romeo P2. The Italian won, with Chiron 2nd and Conelli 3rd.

Not even Varzi in a Bugatti Tipo 51 could keep the wolves at bay in the 1931 Targa, which was won by Tazio Nuvolari in an Alfa Romeo 8C 2300, with Baconin Borzacchini 2nd for Alfa and Achille 3rd. The result was precisely the same in 1932, with the win going to Nuvolari in an Alfa Monza. Borzacchini came 2nd in an identical car, and the Varzi-Chiron duo 3rd in a Tipo 51.

Photo: Yves Naquin

After years of mind-boggling success, the Tipo 35 and its twin overhead camshaft descendent 51 gave way to the eight-cylinder in-line T59, which was unable to make much of an impression on the sport’s new head honchos, first the Alfa Romeo P3, then the Auto Unions and Mercedes-Benz, as they blitzed their way to victory right up to the start of the Second World War.