While we were on our way, we started talking about my favorite subject. He then told me he had a 1959 Triumph TR3A roadster, and that it was restored, and all original and correct. It occurred to me that whoever said everything happens for the best may be right, because my brain scan was normal, and on the way home Bob offered me a drive in his Triumph. I jumped at the opportunity.

Bob pushed the starter button on his British racing green Triumph roadster and the engine barked to life with a throaty growl. He let it warm for a minute or two, then flicked it into reverse and backed it out into the sunlight. It is beautiful, and looks factory fresh. He motioned for me to get in, and I did, but it took maneuvering on my part. I’m glad I wasn’t being filmed. I reached down and opened the low-cut door, and then cantilevered my posterior in and back onto the bucket seat. I then managed to pull my legs up and in, one at a time, and settle back into the cozy but comfortable seat.

You don’t actually climb into a TR3. Instead you sort of pull it on like a boot. Once in, I am amazed that I can reach out and put the palm of my hand on the pavement. And also because of my six-foot plus height, the windshield frame is just above my eye level. I feel like I am sticking up out of the car. Bob jumps on the gas and we were off with a startling burst of acceleration. I am not talking about muscle car madness, but I am pushed back in the seat never the less.

Bob drives over to a nearby bay for our photo op and we gather a small crowd of onlookers. The younger people had lots of questions. The little car’s sporty no-nonsense, low-slung styling and masculine rumble are definitely attention getters.

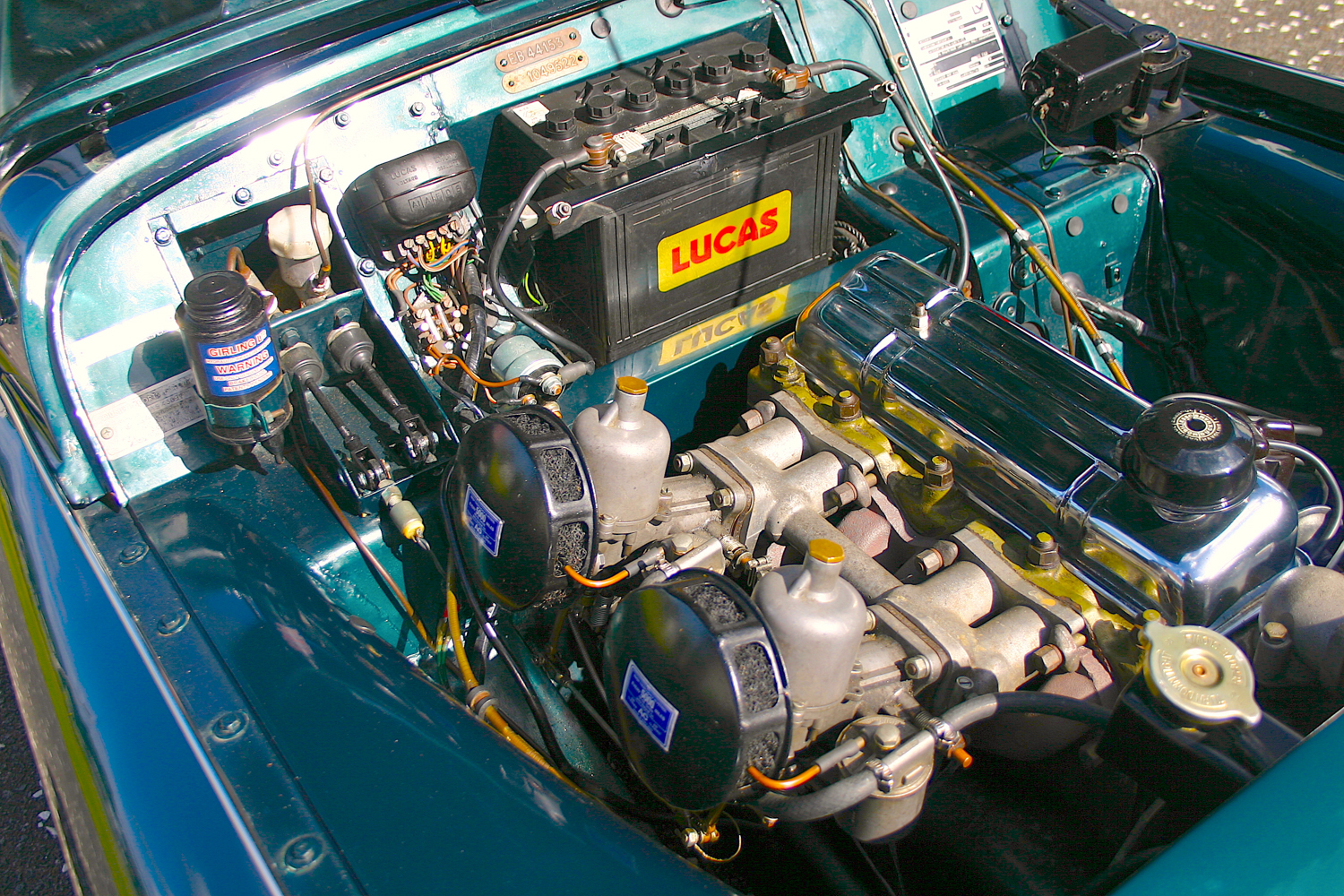

I marvel at the unique details of the car that I discover upon closer scrutiny. The hood is opened using a T-shaped key to turn the latches a quarter turn on each side, similar to the Dzus fasteners used on racecars. The engine is a 2,138-cc (130.5 cubic inch) inline, four-cylinder, overhead valve, pushrod type, with free flowing manifolds and twin SU H6 carbs feeding it.

There is the usual British Lucas electrical system with a plethora of wires going to the voltage regulator, and a Lucas labeled battery even though the company has been gone for years. The fuel tank is behind the cockpit, and the gas cap is centrally located for quick fills from either side. And under the trunk is a compartment for the spare tire, accessed from the rear using the same key as for the hood.

The convertible top is detachable, and held on to its irons with snaps, leaving just the irons to be folded back behind the seat. There are interior pull cables in the doors, but no interior door handles, and no roll up windows. This is a fair weather car, built for fun and excitement, but there are detachable side curtains for use during inclement weather. A hard top was also available at extra cost, but there were few takers, and Bob tells me they made the car seem claustrophobic and noisy when in use.

The TR3A’s accouterments seem quite Spartan today. But what passes for a sports car now is actually almost a mockery of the term. Originally, sports cars were built to enhance the enjoyment of driving, and the perception of speed. In a modern “sports” car you can do 80 miles per hour and not feel like you are going fast, but doing the same speed in a TR3A feels like you are going warp nine.

Also, these days, so called “sports” cars have all the sissy comforts, such as automatic transmissions, air conditioning and GPS; plus entertainment centers and a host of other electric furbelow. And they ride like luxury cars. Engine noise is discretely implied, and little thought is given to such factors as power-to-weight ratios or spirited handling. In short, they are “sports” cars for the limp wristed and effete.

Classic British sports cars were geared to the amateur racer who wanted to dice around the hay bales at the local temporary airport racecourse on the weekends, and be competitive with the likes of the MGA, four-cylinder Porsches and smaller Austin-Healeys. Aficionados didn’t need, or want, all that other nonsense. Of course, the Triumphs were no match for the Jaguars and Ferraris, but they were also not nearly as expensive and dangerous either.

The Great Depression of the 1930s all but killed American sports cars, and the surviving automakers concentrated on family sedans and big comfortable cars after World War II to answer the needs of baby boomer families. But while the G.I.s were in Europe, they discovered the small, nimble sports cars that the better off young swains in the U.K. enjoyed. And when our boys returned, they brought the enthusiasm for sports roadsters back with them.

It didn’t take long for the exciting little British machines to catch on in a big way. So much so, that by the time our TR3A was being produced, over 85 percent of production went to the United States, and the same was generally true for the MGs, Jaguars and other British sports cars of the era. In short we loved them.

Bob Birdsall’s Triumph is actually a rarity by virtue of the fact that it has the steering wheel on the right-hand side, making it a car intended for Britain, or certain commonwealth countries. Some 85-percent-plus of the 58,287 strong TR3A production run went to the United States and it is estimated that about 9,500 remain today. Bob’s TR3A was destined for Singapore, and remained for a number of years before being shipped to Japan, where it was raced during the 1970s and ’80s. It fit right in because the Japanese patterned their early auto industry after the British, and they too drive on the left.

So what is it like to drive? After our photo shoot Bob tosses me the keys. I open the door and slide my left leg into the foot well, and then drop my derriere into the seat. And then I bring my right leg around, hug it to my chest, pivot, and then extend it into the foot well which is wide enough for my two feet and nothing else. The pedals are tiny, and close together, so I do a little tap dance to make sure which pedal is which before starting the car. It would take a little getting used to, but this arrangement would be ideal for heel and toe shifting.

The engine comes to life instantly and settles into a sonorous rumble. The instrument panel is replete with a compliment of handsome analog gauges that assure me all is as it should be. I release the old style hand brake lever, and flick the short, precise gearshift into low and we are off. The diaphragm clutch is hydraulically actuated and smooth and sure.

Acceleration is instant, and surprising thanks to the bottom end torque of the car’s engine, which was derived from a tractor motor originally, but reworked by Donald Healey, and was also used (albeit detuned) in the light delivery vans that were built on the same assembly line as the sports cars. So it is not delicate or high strung in the least. It makes good torque at 2,000 rpm and is even better at 3,000 to 4,500 rpm.

Shifting is sure and swift thanks to the sturdy short lever and top-loading transmission. The transmission is effectively a seven speed thanks to the optional solenoid-activated Laycock de Normanville overdrive that splits the top three gears with a step on the throttle. The clutch is smooth, and easy to operate.

Handling is flat and sure. The ride is a bit harsh on bumpy roads, and the steering is very responsive, though it requires muscle at low speeds. But the best part of driving Bob’s TR3 is the feeling of being out in it and part of things, almost like being on a motorcycle, and seeing the world flash by. I’ve done 150 mph in a Corvette ZO6 and not felt the sensation of speed that you get in a vintage British sports car at half that speed.

Birdsall tells me that not only has his car been most of the way around the world, but it has been restored twice over its 60-plus years as well. It started life white with a red interior, and was repainted red with a black interior when it was raced, and then it was done up in its present British racing green with black trim as it is today. Also, while it was in Japan, the engine was breathed upon with porting, a hotter cam, and stiffer valve springs, which Bob has since replaced with the original types so as not to wear out the cam. The latest restoration was done professionally in New Zealand, and Bob bought it in 2010.

Triumph Motors evolved out of the Bettman Bicycle Company in Germany which opened an assembly plant in Coventry, England, in 1899. The company was renamed the Triumph Cycle Company in 1897. And then, in 1902, they began making motorcycles. At first they purchased their engines from an external source, but their motorcycles sold well and they soon began making their own motors.

Things went well, and with the advent of World War I the company received large orders from the British army for their Model H 550-cc bike, making them the largest manufacturers of motorcycles in Britain. The company continued to do well for the next ten years, and in 1930 its name was changed to the Triumph Motor Company. At that point, they decided to produce more expensive sporty cars, and introduced the Southern Cross and the Gloria. And once again, at first they used engines purchased from an outside source. But then, in 1937, they began production of their own power plants designed by Donald Healey.

The depression hit the company hard however, and to stay afloat the bicycle and motorcycle business was sold to a competitor, Ariel, to become Triumph Engineering Ltd in 1936. The car company continued to produce their cars until the manufacturing plant in Coventry was flattened, in 1940, during the battle of Britain.

And then, in 1944, the remnants of the Triumph Motor Company, including the name, was purchased by the Standard Motor Company and the name changed to the Standard Triumph Motor Company. Thus, Triumph became a subsidiary of Standard, who had been supplying engines to Jaguar since 1938.

After the war, Standard decided to revive the Triumph marque for their line of sports cars. And, in 1953, the TR2 debuted and was a runaway success in the United States. It was the beginning of the long TR series that went from the TR2 all the way to the short-lived TR8 in 1981, which was really a TR7 with a V8 in it.

Birdsall’s TR3 was a direct development of the TR2 in 1955, but with a slightly bigger engine and wide mouth grille. The TR3A came out in 1957, but that was never an official designation. It had a bit more power and front disk brakes, which was a first in a production car. The American auto company Crosley Motors had disk brakes earlier, but they were not successful, and the company went back to conventional drum brakes before it folded in 1952.

Triumph was purchased by Leyland Motors in 1960, and wound up being part of the British Leyland conglomerate in 1968, along with Rover and Jaguar. Triumph badged Hondas continued to be assembled until 1984, when the name was finally retired. The trademark is now owned by BMW along with other bits and pieces of the once great British auto industry.

So what makes Bob’s TR3A so special? Well, perhaps partly because it is today what it was back when it was built, and that is a fun, rugged little sports car that is still affordable at between $18,000 for a good driver, to perhaps as high as $35,000 for a restored one. And it is economical at 25– 28 miles to the gallon, depending on your driving style. Also, parts are still available from sources such as Moss Motors in California, and a number of sources in the U.K. that you can find on the Internet.

Is it terrifyingly fast? No, although a 125 mph top end is not to be scoffed at. Is it smooth, quiet and cushy? No. You would definitely not want to drive it across west Texas on the interstate. But on the twisty two-lane country roads for which it was designed, it is unsurpassed for driving thrills and excitement. The only thing that might be more thrilling in such circumstances would be a Triumph motorcycle, but having fallen off of one in my misspent youth, I will stick with the TR3A. Everything happens for the best.

1959 Triumph TR3A Technical Specifications:

| Engine Location : | Front |

| Drive Type : | Rear Wheel |

| Body / Chassis : | Steel body on steel frame |

| Production Years for Series : | 1957 – 1962 |

| Price : | $2,685-$2,825 |

| Weight : | 2020 lbs | 916.257 kg |

| Length : | 151.0 in | 3835 mm. |

| Width : | 55.5 in | 1410 mm. |

| Height : | 50.0 in | 1270 mm. |

| Wheelbase : | 88.0 in | 2235 mm. |

| Front Track : | 45.0 in | 1143 mm. |

| Rear Track : | 45.5 in | 1156 mm. |

| Engine : | Cast Iron, inline, 4-cylinder |

| Displacement : | 2138 cc | 130.5 cu in. |

| Power : | 110 BHP (73.6 KW) @ 5000 RPM |

| Torque : | 117 Ft-Lbs (159 NM) @ 3000 RPM |

| Bore : | 3.3 in | 83 mm. |

| Stroke : | 3.6 in | 92 mm. |

| Compression : | 8.5:1 |

| Main Bearings : | 3 |

| Transmission: | 4 speed Manual with overdrive |

| 0-60 mph : | 12.55 seconds. |

| Top Speed : | 125 mph |

| Triumph Production for 1959 : | 22,922 |

| TR3A Production (1957-1962) : | 58,236 |