We posed the question two issues back, “Who are the two Americans who would have been most likely to succeed in Formula One, but never tried?” We gave early-1950s Cunningham ace Phil Walters as our first choice and asked you to guess the other. Well, here are the results.

Rick Mears’ name came up often and indeed, the “what-ifs” are intriguing. In 1979, Mears won the Indy 500 and the first CART championship in his first full year with car-owner Roger Penske. Jackie Stewart touted the Californian to Brabham team owner Bernie Ecclestone, and in 1980, Mears tested in Europe and in the U.S. against Brabham driver Nelson Piquet. At Paul Ricard, Mears was only a half second behind the talented Brazilian. At Riverside Raceway, he was two to three seconds faster. Regardless, Mears passed on the opportunity, deciding to stay in CART with Penske. The following year, Nelson Piquet was World Champion in the Brabham. Makes one wonder, eh?

By far, the most popular choice was A.J. Foyt. And why not? Super Tex could drive the wheels off of anything. In 1964, the then 29-year-old Indianapolis champion did get an offer to drive a works BRM in Formula One, but Foyt too preferred U.S. racing. His road racing career was not extensive, but A.J. did manage to win the 24-Hours of Le Mans with Dan Gurney in 1967. A little known fact is that two weeks later at Spa, Belgium, when Gurney became the first American driver to win a Grand Prix in a car of his own manufacture, none other than Super Tex was entered as the driver for the second Eagle. It never happened, but Gurney is one who would like to have seen Foyt in Formula One.

“You know,” he told us, “that was a time in the mid- to late-sixties where Mario and A.J. Foyt were locking horns. And A.J. was also a legitimate superstar at the time. He was not a road race specialist, but he was, nevertheless, a great racing driver… And a great character…..It would have been interesting.”

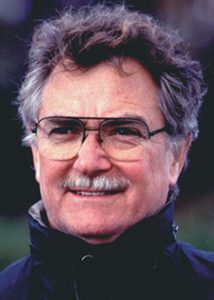

Yes, it would have been, but there was another American in the early- to mid-sixties who had already matched up very well against F1’s best and, we think, just might have been even a better choice: one Rufus “Parnelli” Jones.

Jones cut his teeth in jalopies on Southern California bull rings in the 1950s and quickly got a reputation for an aggressive banging-and-bumping, all-or-nothing driving style. In truth, at first, Parnelli was more spectacular than successful.

“I was not,” Jones admits, “a natural. I had a lot of desire. A lot more than I had talent. I really learned the hard way. I wrecked my car week after week, you know, because I had all this desire and no talent. Anyway, finally a guy saw something interesting in me and he says, ‘Look, I’ll build an engine.’ I blew my engine up, and I didn’t have any money to fix it. And he says, ‘I’ll build an engine for your car if you’ll just listen to me.’ So I says, ‘Hey, yeah, yeah, anything.’ So he did and all he said was, ‘Quit trying to win the race in the first lap. Slow down, take your time, take your time.’ I went out, set quick time with his engine and started winnin’ races from that day on.”

Race promoter and car owner J.C. Agajanian soon recognized Jones’ awesome talent and took him to the big time. By 1960, Jones was crowned Midwest sprint car champion. The same year, Foyt won the Eastern series. For 1961, USAC combined the two championships and a ferocious three-way struggle ensued between the top three drivers, A.J. Foyt, Jim Hurtubise, and the California sensation, Parnelli Jones. Those three drivers won 21 of the 24 races run that season – and Jones won the championship. He made it two in a row the following year.

In his first appearance at Indy in 1961, Jones was Rookie of the Year. He qualified fifth in Aggie’s car and was leading the race when magneto problems took him out. The following year, he put Aggie’s car on the pole with the first 150-mph qualifying run at the Speedway and proceeded to run away from the field until a worn brake line slowed him to seventh at the end.

I had the good fortune of being at Indianapolis in 1963 to witness the epic battle between Jones in Aggie’s roadster and Dan Gurney and Jimmy Clark in the nimble mid-engine Lotus-Fords. Being an F1 snot, I rooted for Gurney and Clark, but there was no question that Jones, again starting from pole position, was the fastest man on the track and deserved his victory. Colin Chapman was not pleased, but he was impressed.

In 1964, Clark was on the pole in a more powerful Lotus-Ford. Jones qualified fourth, the fastest of the Offy roadsters. He was again leading when a pit fire put him out after 55 laps. Jones began to cut back on his open-wheel racing that year, but in August, Colin Chapman offered Foyt and Jones rides at Milwaukee. Regular Lotus works driver Jimmy Clark was racing in Europe.

While Foyt qualified third and DNF’d in the race, Jones pulverized Clark’s qualifying record from the previous year and set a new race record to win easily. Three weeks later at Trenton, Clark was back, and Chapman asked Jones to drive the second car, but with one proviso.

“Chapman came to me and he says, ‘You know, Jimmy’s my number-one driver, so if you guys are running one-two, I would expect you to let Jimmy win. You know what I mean?’ And I says, ‘Well, I’ll tell you what, Mr. Chapman. We don’t do it that way over here, but I’m going to be taking it easy for the first 150 laps. The last 150, I’m gonna be on the gas.’”

In his second “rear-engine” drive, Jones put the Lotus on the pole with a new track record, while Clark struggled in seventh. In the race, “moving over” was never an issue, as Jones again won going away. A few weeks later, I was at Riverside Raceway when Parnelli Jones drove a Shelby King Cobra. It was his first road race. In addition to Americans Dan Gurney and Richie Ginther, the Times Grand Prix field was studded with a number of foreign F1 drivers, among them, Jimmy Clark in a works Lotus-Ford. Was the rookie road racer Jones intimidated?

“No, I wasn’t intimidated by anyone. I would say if there was ever anybody like me in my early days, it would be Earnhardt. I always felt like I could drive better than anyone else. I mean, when you have that much confidence….”

Jones blew his engine in practice, and in the short race on Saturday, he was undeniably quick, but spun several times. And every time he did, he’d make these heroic charges back toward the front, passing one car after another. This side, that side, it didn’t seem to matter. And then he’d spin again. Regardless, Jones managed to finish and then to qualify third for the big race on Sunday. Obviously, Mr. Jones could turn right, too.

“It was like a duck getting into water. It came very natural to me, much different than the ovals did. And I won the race. I just kept from spinnin’ it out!”

Colin Chapman was convinced and tried to persuade Jones to come to Europe to drive an F1 Lotus the next season. No sale.

“The reason I didn’t go to Formula One, first of all, I wasn’t fond of traveling and I thought if I went over there, it’d take a year of learning the racetracks. And Formula One didn’t carry the prestige it does today. No disrespect, but I didn’t have a lot of respect for them at the time. You know what I mean? I think they were great race drivers, but at the time, I just thought they were gentlemen drivers. And we didn’t come up that way, you know, runnin’ midgets and sprint cars and stock cars. You know, we were rough, dirty, dirt-track drivers, that sort of thing.”

Parnelli laughs out loud at his own imagery, but then adds, “If you could get a hold of Jackie Stewart, he’d tell you. He made the statement that I could have done really well in Formula One.”

We don’t think there’s any doubt.